UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Primary Source Sets

Primary Source Sets

Primary source sets are organized by topic or theme and include a variety of primary source types across a spectrum of levels. Historical background for the set and details about each document are also included.

Utah Women in World War One

World War I involved women in Utah and throughout the nation in new capacities. For the first time in U.S. history, women from every class and community had the opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and contribute directly to the war effort. Utah women witnessed the violence of the war firsthand near the front lines as telephone operators, nurses, ambulance drivers, canteen workers, and Salvation Army workers. Many entered the workforce in unprecedented ways to fill jobs they had not been able to access before the war. Many others joined in community organizations and clubs on the homefront to support the war effort through volunteer service. Some women used the opportunity to advocate for important causes and continue blazing the trail toward universal civil rights and social justice. Whether these new experiences brought them to the front lines, the workforce, the homefront, or to advocacy, every woman in Utah was deeply affected by the war. As women engaged in the military, the economy, and their communities in new ways, they expanded the roles traditionally open to women

World War I involved women in Utah and throughout the nation in new capacities. For the first time in U.S. history, women from every class and community had the opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and contribute directly to the war effort. Utah women witnessed the violence of the war firsthand near the front lines as telephone operators, nurses, ambulance drivers, canteen workers, and Salvation Army workers. Many entered the workforce in unprecedented ways to fill jobs they had not been able to access before the war. Many others joined in community organizations and clubs on the homefront to support the war effort through volunteer service. Some women used the opportunity to advocate for important causes and continue blazing the trail toward universal civil rights and social justice. Whether these new experiences brought them to the front lines, the workforce, the homefront, or to advocacy, every woman in Utah was deeply affected by the war. As women engaged in the military, the economy, and their communities in new ways, they expanded the roles traditionally open to women

Check out all of our lesson plans, storymap, bios, and articles related to WWI here.

Primary Source Set

National WW1 Museum and Memorial Collections.

Photo: “Hello Girls” near the Front Lines, October 5, 1918

Photograph of telephone operators, or “Hello Girls,” with the U.S. Army Signal Corps. These switchboard operators were stationed at General Pershing’s headquarters, only 3 kilometers from the trenches in France in 1918. They faced grueling hours and dangerous conditions, as indicated by the army helmets and gas masks hanging on the back of each of their chairs. This elite unit of 223 women in WW1 were the first women to wear U.S. Army uniforms, rank insignia, and tags, and they were subject to court martial and took the army oath, but when they returned from their service overseas the government denied them veteran status and benefits for decades. Click here for our 4th-6th grade lesson plan about the Hello Girls.

Suggested questions: The Hello Girls were finally granted veteran status in 1977 after decades of advocacy. Why does veteran status matter? How did the WW1 army switchboard operators pave the way for women in the military today?

Article: “Salt Lake Girls Join U.S. Navy,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, December 2, 1917, p. 9.

Article: “Salt Lake Girls Join U.S. Navy,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, December 2, 1917, p. 9.

During World War One, six Utah women were among the first to ever enlist in the United States Navy. They served their country in this unprecedented expansion of women’s role in the military. By entering the naval workforce and filling vital non-combat positions on the homefront, these female yeomen helped facilitate more men going overseas and paved the way for women’s military service.

Suggested questions: During WW1, women began wearing official uniforms in many capacities throughout society for the first time. What types of uniforms did women wear, and what was the significance and impact of those uniforms on women’s roles?

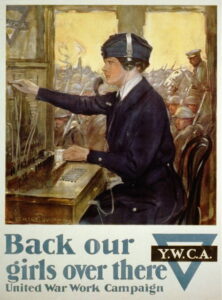

Object: Banner with the Motto of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, ca. 1924, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Object: Banner with the Motto of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, ca. 1924, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

This banner features the inspiring motto of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC): “Lifting As We Climb.” The Western regional chapter of this coalition of Black women’s clubs was formed in 1904 in Salt Lake City by Elizabeth Taylor. It helped coordinate the efforts of many different women’s clubs in Utah’s Black community. By WW1, several affiliated clubs and organizations – such as the segregated Amity Red Cross unit – contributed in meaningful ways to the war effort and to the community. As president of the Utah Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1918, Gertrude Lancaster represented Black women and made sure their wartime charity efforts were officially recognized and recorded by the Utah State Council of National Defense. *Note: During the early 1900s, use of the term “colored” when referring to Black Americans was considered standard and neutral language, but the term is now widely understood to be offensive

Suggested questions: The Black women’s club movement coincided with the larger national women’s club movement at the turn of the century. What can we learn from the ways that black women’s organizations both overlapped with and were separated from the mainstream movement? What is the meaning and significance of the motto “Lifting As We Climb” for Black women’s organizations in the early twentieth century?

Photo: Auto Supply Workers, 1918, Utah Historical Society.

Photo: Auto Supply Workers, 1918, Utah Historical Society.

The war increased demand for agricultural, industrial, and military production, but there was a shortage of workers because so many men were soldiers. This opened new employment opportunities for women in the workforce. Many Utah women started working as factory employees, cannery workers, elevator and switchboard operators, and stenographers (typists). This photograph of female employees standing outside the Automobile Supply Company store on Main Street in Salt Lake City, on September 14, 1918, depicts women working in industrial labor jobs that were generally restricted for women before the war. Women such as Eleanora Streadbeck advocated for the rights of female laborers during this transitional time.

Suggested questions: What new challenges might have arisen for employees and employers as women entered the workforce in larger numbers and in new industries during the war? What benefits might have resulted from this expansion of employment opportunities for women?

Illustration by Brooke Smart.

Speech: President Wilson’s Speech to the U.S. Senate on the Nineteenth Amendment, September 30, 1918 (excerpt) [Download PDF here]

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson did not always support a constitutional amendment protecting women’s suffrage (meaning the right to vote). Prior to the war, President Wilson had argued that women should not vote or that women’s voting rights should be decided separately by each state. Suffrage advocates (including two from Utah!) even spent over two years picketing in front of the White House because of his lack of support. This speech strongly urges the Senate to support a national suffrage amendment and calls such support “vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war,” a message that was in stark contrast to his earlier position. Within a year after this speech, the U.S. Senate passed the 19th Amendment in June 1919. Women’s right to vote officially became law throughout the United States in August 1920.

Suggested questions: How does this speech demonstrate the president’s evolution in his support for women’s right to vote? How did the contributions of women to support the war effort and to advocate for their rights help impact this shift in the president’s opinion?

Courtesy of the Utah Historical Society.

Photo: University of Utah Red Cross Unit, 1918.

During World War 1, millions of women on the home front participated in organizations such as the Red Cross, YWCA, Salvation Army, Relief Society, and many more to arrange liberty bond drives, initiate food conservation programs, host fundraising events, and sew and knit hospital clothing, socks, and bandages for soldiers overseas. Gold Star Mothers like Annie Payne Howard also spearheaded efforts to memorialize the many lives lost during the war. The Red Cross was one of the most widespread and effective war relief organizations in Utah and throughout the world. This Red Cross unit at the University of Utah, along with the Amity Red Cross Unit led by Gertrude Lancaster, demonstrates the ways that women in different communities and phases of life all contributed to the war effort through the Red Cross and other women’s organizations.

Suggested questions: The Committee on Women’s Work in the World War, which was part of the Utah State Council of Defense, helped coordinate the many wartime activities of the various women’s organizations with military-like efficiency. In what ways do you think knitting and other women’s war efforts impacted the nation during wartime and beyond? How might women’s involvement in organized service have impacted the women themselves?

Women and Lawmaking: How a Bill Becomes a Law

All citizens of the state of Utah have the right to vote. Some elections involve voting for people to serve in the Utah State Legislature. The Legislature meets every January in order to establish laws for our state, and is made up of state Representatives and state Senators. Establishing laws is a multi-step process, the main steps are outlined below. While most of these steps must be taken by state representatives or senators within the annual legislative sessions, input from the public along with advocacy from community organizations influences how the laws are made as well.

Learn more about how Utah women influenced the process of law-making during the Statehood Era (1896-1920) from the following primary sources.

Developed - Drafted - Introduced - Sent to Committee

Before a law is ever made, the idea for the law must be developed. Ideas for potential laws come from many sources, including public input or community advocacy organizations. In order to be considered by the state legislature, this idea must then be drafted into a bill. After it is drafted, a legislator introduces the bill in either the state House of Representatives or the state Senate. The bill is then referred to a legislative committee. Members of the legislature work on different committees, where smaller groups of elected officials review the details of the bill and decide if it should be voted upon by the entire chamber of the legislature, either the House or Representatives or the Senate. If the committee recommends the bill, it is returned to the floor of the House or Senate. If the committee does not recommend a bill, it is considered killed in committee.

- An idea is developed prior to the legislative session

Trinity African Methodist Church in Salt Lake City, a Black church established in the 1890’s and still in existence today, was affiliated with many community organizations created by and for Salt Lake’s Black community. One of these organizations was the W.T. Vernon Literary association. Elizabeth Taylor, a key member of the Trinity AME congregation and member of the W.T. Vernon Literary association, was an important community organizer, activist, and suffragist at the time of Utah’s statehood. During this time period, many public buildings and businesses were segregated, meaning there were separate businesses and public spaces (ie. inns, restaurants and hotels) for Black people and white people. Black people did not have access to all the accommodations that white people did. Elizabeth “Lizzie” Taylor advocated for equal access to all public spaces in Salt Lake for all residents, regardless of skin color.

2. A bill is drafted and then introduced in either the state House of Representatives or state Senate.

In 1911, Senator Smith from Salt Lake introduced Senate Bill 58, by request, on the floor of the Utah Senate. The bill advocated for equal access to public accommodations for all persons living in Utah.

What similarities do you notice between the language of the city ordinance (law) Elizabeth Taylor petitioned for in 1910 and Senate Bill 58 from the 1911 Legislative session?

This Salt Lake Tribune article reports that in 1911, the advocacy of the Black community in Salt Lake led to the creation and drafting of Senate bill 58.

While the Senate bill does not directly mentioned who was involved, what information does this newspaper article provide about who worked for the creation and drafting of Senate bill 58 in 1911?

Note: Language used in this primary source to describe the collective Black community of Salt Lake reflects common terms from this specific time period that are no longer used in our current-day. Take time to educate yourself and your students about the appropriate use of and context of such terminology.

3. A bill is sent to a legislative committee.

Senate Bill 58 of the 1911 legislative session was referred to the judiciary committee. The judiciary committee is in charge of bills that deal with the court and law enforcement. The bill was killed in committee and never returned the floor of the Utah senate for debate or vote.

Returned to Floor - Debated - Voted Upon

Legislative committees decide if a bill will return to the floor of the House/Senate. The bill is then debated and voted upon by that chamber of the legislature.

4. A bill returns to the floor and is debated and voted upon.

Martha Hughes Cannon served as a Utah state Senator from 1897-1900. In 1897, she introduced Senate bill 31, to protect women and girls in the workplace. She also served as chairman of the Public Health Committee, which reviewed and recommended the bill return to the floor of the Utah senate. On 4 February 1897, the bill passed the Utah senate with a vote of 16 to 1.

Repeat Process in Opposite Chamber

Once a bill is passed in one chamber of the legislature, it is then sent to the opposite chamber where the bill goes through the same process all over again. Many times, Representatives and Senators work together to get important bills passed through both chambers of the legislature. If a bill does not pass both chambers of the legislature it cannot continue the process of becoming a law

5. A bill is sent to the opposite chamber of legislature, where the bill repeats the process over again.

Sarah Anderson was elected to the Utah House of Representatives in 1896 by the people in Weber county. During the 1897 legislative session, Rep. Anderson worked alongside Martha Hughes Cannon to pass Senate bill 31 in the state House. Both women served as chairperson of the Public Health committee in their respective chambers of the Utah Legislature, and both recommended that Senate bill 31 pass. The Utah House of Representatives voted in favor of the bill on 13 February 1897.

Representative Alice Merrill Horne was elected in 1898. She worked during the 1899 legislative session to pass a bill creating a state Art Institute. She introduced the bill in the House of Representatives, but then later withdrew her House bill in favor of a Senate bill. The Senate bill was an exact copy of Rep. Horne’s House bill.

Representative Horne encouraged her fellow elected officials to vote in favor of the bill by pinning yellow flowers on the lapels of male legislators the day of the vote to remind them that she had the support of female voters behind her.

This article from the Salt Lake Tribune reports on the work of Rep. Horne during the legislative session.

The Broad Ax, one of several Black newspapers in Salt Lake at the time, made special mention of Representative Horne’s important efforts.

Governor Approval

If a bill passes both chambers of the legislature, it is sent to the Governor for approval. After the Governor signs the bill it becomes a law. If the governor disapproves of the bill, they veto it and it doesn’t become a law. If the legislature has enough votes to override the veto, the bill can still become a law.

Governor Olene Walker is the only woman to serve as Governor of Utah. She was elected as Lieutenant Governor in 1993 alongside Governor Mike Leavitt. When Gov. Leavitt left office to serve as the head of the National Environmental Protection Agency, Olene Walker was sworn in as Governor in 2003 to finish the Leavitt/Walker term of office. Utah has yet to elect a woman to serve as Governor of the state.

This 2004 Executive Order, establishing a State Commission on Literacy, shows Governor Olene Walker’s signature.

"...Ask Council to Stop Discrimination" SL Tribune 24 June 1910, p. 16

"...Ask Council to Stop Discrimination" SL Tribune 24 June 1910, p. 16

Senate Bill 58, 1911 Utah Legislative Session, p. 3 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1911 Session: Bills 58-59)

Senate Bill 58, 1911 Utah Legislative Session, p. 3 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1911 Session: Bills 58-59)

"Measure...Introduced in Senate" SL Tribune, 21 January 1911, p. 3

"Measure...Introduced in Senate" SL Tribune, 21 January 1911, p. 3

Senate Bill 58, 1911 Utah Legislative Session, p. 5 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1911 Session: Bills 58-59)

Senate Bill 58, 1911 Utah Legislative Session, p. 5 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1911 Session: Bills 58-59)

Senate Journal, Second Session of the Utah Legislature, 1897, 25th Day, p. 137

Senate Journal, Second Session of the Utah Legislature, 1897, 25th Day, p. 137

Senate Bill 31, 1897 Utah Legislative Session, p. 1 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1897 Session: Bills 28-31)

Senate Bill 31, 1897 Utah Legislative Session, p. 1 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1897 Session: Bills 28-31)

Senate Bill 31, 1897 Utah Legislative Session, p. 2 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1897 Session: Bills 28-31)

Senate Bill 31, 1897 Utah Legislative Session, p. 2 (Series 428 | Legislature. Senate | Working bills | 1897 Session: Bills 28-31)

House Bill 124, 1899 Utah Legislative Session, p. 1 (Series 432 | Legislature. House of Representatives | Working bills | 1899 Session: Bills 121-125)

House Bill 124, 1899 Utah Legislative Session, p. 1 (Series 432 | Legislature. House of Representatives | Working bills | 1899 Session: Bills 121-125)

House Bill 124, 1899 Utah Legislative Session, p. 6 (Series 432 | Legislature. House of Representatives | Working bills | 1899 Session: Bills 121-125)

House Bill 124, 1899 Utah Legislative Session, p. 6 (Series 432 | Legislature. House of Representatives | Working bills | 1899 Session: Bills 121-125)

"Pass Alice Art Bill" SL Tribune, 10 March 1899, p. 5

"Pass Alice Art Bill" SL Tribune, 10 March 1899, p. 5

"Our Reflections on Third Legislature" Broad Ax, 18 March 1899, p. 1

"Our Reflections on Third Legislature" Broad Ax, 18 March 1899, p. 1

2004 Executive Order, Utah Governor Olene Walker, 22 December 2004 (Series 85039 | Lieutenant Governor | Governors' executive orders and proclamations | Executive Order issued 12/22/2004)

2004 Executive Order, Utah Governor Olene Walker, 22 December 2004 (Series 85039 | Lieutenant Governor | Governors' executive orders and proclamations | Executive Order issued 12/22/2004)

The following websites offer online access to original sources in Utah history

- The Utah Division of Archives and Records Services provides digital access to working bills of the Utah Legislature from 1896-1989

- Senate Working Bills (Utah State Archives Series 428) can be found here or at https://archives.utah.gov/digital/428.htm

- House’s Working Bills (Utah State Archive Series 432) can be found or at https://archives.utah.gov/digital/432.html

- Many Utah newspapers have been digitized and can be accessed here or at https://digitalnewspapers.org/

- A database of all past and present Utah Legislators, searchable by year, can be found here or at https://le.utah.gov/asp/roster/roster.asp

- The Utah Office of Legislative Research and General Counsel offers a PDF of “How a Bill Becomes a Law in Utah”. It can be found here or at https://le.utah.gov/lrgc/billtolaw.pdf

Women and the Railroad

Completed with a ceremonial golden spike driven at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad brought technological, economic, and cultural changes to Utah Territory. Despite the fact that women do not appear in photographs of railroad workers and businessmen celebrating the project’s completion, they are part of the story, too. Learn more about how they were involved and how the railroad impacted them through the use of primary documents

Primary Source Set

Quote from Godey’s Lady’s Book, August 1869

Godey’s Lady’s Book was the most popular magazine in America in the 1860s. In August 1869, the magazine reported on the completion of the transcontinental railroad in Utah and noted: “This great work was begun, carried on and completed by men only. No woman has laid a rail: no woman has made a survey. The muscular force and the intellectual guidance have come alike from men.” While the excerpt from the Godey’s Lady’s Book states that no women were involved in the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, this was factually inaccurate. How were women involved in the building of the railroad? What motives might the magazine have for printing this information? Why would they print this excerpt in a women’s magazine?

Godey’s Lady’s Book was the most popular magazine in America in the 1860s. In August 1869, the magazine reported on the completion of the transcontinental railroad in Utah and noted: “This great work was begun, carried on and completed by men only. No woman has laid a rail: no woman has made a survey. The muscular force and the intellectual guidance have come alike from men.” While the excerpt from the Godey’s Lady’s Book states that no women were involved in the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, this was factually inaccurate. How were women involved in the building of the railroad? What motives might the magazine have for printing this information? Why would they print this excerpt in a women’s magazine?

Harper’s Illustration

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Harper’s Illustration portraying a “romance” between a female and male telegrapher. Women telegraphers were often portrayed in media as taking the job as a way to find husbands.

Telegraph Belonging to Katherine Fenton Nutter

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Telegraphy was often young women’s first job. The telegraph belonged to Katherine Fenton Nutter, wife of Preston Nutter, one of Utah’s most successful cattle ranchers through the turn of the century. Katherine was the manager for the Colorado Springs Postal Telegraph Company Station through the 1890s and later relocated to the Nutter Ranch in Nine Mile Canyon in 1908 after marrying Nutter. The ranch also served as a telegraph relay station between Fort Duschene and Price from 1886 to 1907. It has been recorded that Katherine and Preston used this telegraph at their ranch. Katherine also owned land of her own and ran the cattle ranch after her husband’s death.

Utah Women in Medicine

Board of the Deseret Hospital.

The railroad made it possible for Utah women to travel East to attend colleges and universities. Utah women were some of the first to graduate from medical schools. They returned to Utah and set up medical practices and opened the women-run Deseret Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Suffragists Traveling & Organizing via the Train

Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

This is the original Central Pacific/Union Pacific train station in Corinne, Utah. It is likely that Susan B. Anthony arrived and left Utah through this train station, using the recently completed Utah Northern to get to Salt Lake City.

Group of State Presidents & Officers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association 1892. Utahns Emmeline B. Wells and Sarah Kimball were in attendance.

Group of State Presidents & Officers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association 1892. Utahns Emmeline B. Wells and Sarah Kimball were in attendance.

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Susan B. Anthony and the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw with leading Utah and Colorado suffragists at a suffrage convention in Salt Lake City, May 1895.

Spread of Ideas

Utah women were able to receive copies of suffrage newspapers and other publications because of the train. Sarah Kimball even mentioned reading Susan B. Anthony’s newspaper The Revolution and how it influenced her ideas on women’s rights.

Utah women were able to receive copies of suffrage newspapers and other publications because of the train. Sarah Kimball even mentioned reading Susan B. Anthony’s newspaper The Revolution and how it influenced her ideas on women’s rights.

Utah Women's Suffrage in 1870

In the late 1860s, as the post-Civil War nation considered the 15th Amendment granting suffrage to African-Americans, debates over women’s suffrage escalated and anti-polygamy sentiment intensified. Following some suffragists’ suggestions to use Utah Territory as a venue to experiment with women’s suffrage, some anti-polygamists proposed empowering Utah’s women with voting rights as a way to end polygamy. Others warned that women’s suffrage in Utah would only increase the political power of Mormons. In January 1870, several thousand Mormon women gathered in Salt Lake City to protest a congressional anti-polygamy bill and to request the right to vote. Just weeks later, the Utah Territorial Legislature unanimously passed a Woman Suffrage Bill giving Utah women voting rights in local and territorial elections. Wyoming Territory had passed women’s suffrage several weeks before in December 1869, so Utah became the second in the nation to extend equal voting rights to women without property or marital restrictions (although national citizenship restrictions still excluded Native Americans and Asian immigrants from voting for many more years). Since Utah held its next two elections before Wyoming did, Utah women became the first to vote in the modern nation. Receiving the vote broadened Utah women’s opportunities to engage in political life and to actively participate in the national suffrage movement.

Primary Source Set

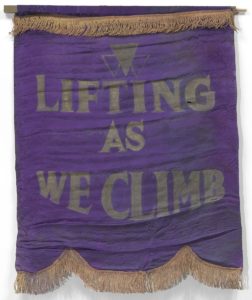

Political Cartoon: “Female Suffrage,” Frank Leslie Illustrated, 1869

This political cartoon refers to the question of granting women’s suffrage in Utah Territory, a proposition that Congress was debating at that time. The image depicts a stern and commanding Brigham Young marching to the voting polls followed by dozens of women carrying babies in one arm and electoral ballots in the other. The women, presumably Young’s wives, follow along in an unending stream with a unified, political motive. The women carry a flag which prominently reads “Straight Dem Ticket,” indicating that if allowed to vote, Mormon women would follow the commands of Young and vote for the Democratic Party. In reality, the Democratic and Republican parties were not established in Utah until the late-1890s. While this “Straight Dem Ticket,” detail is thus historically inaccurate, it was an effective warning that resonated with the Republican majority in post-Civil War America. The caption, “Wouldn’t it put just a little too much power into the hands of Brigham Young, and his tribe?” provides a clear warning that women’s suffrage would only serve to strengthen the political power of Mormons in Utah. Reflecting the racially-charged views of the time, the term “tribe” further cast Mormons as “un-American” and the embodiment of “The Other.”

This political cartoon refers to the question of granting women’s suffrage in Utah Territory, a proposition that Congress was debating at that time. The image depicts a stern and commanding Brigham Young marching to the voting polls followed by dozens of women carrying babies in one arm and electoral ballots in the other. The women, presumably Young’s wives, follow along in an unending stream with a unified, political motive. The women carry a flag which prominently reads “Straight Dem Ticket,” indicating that if allowed to vote, Mormon women would follow the commands of Young and vote for the Democratic Party. In reality, the Democratic and Republican parties were not established in Utah until the late-1890s. While this “Straight Dem Ticket,” detail is thus historically inaccurate, it was an effective warning that resonated with the Republican majority in post-Civil War America. The caption, “Wouldn’t it put just a little too much power into the hands of Brigham Young, and his tribe?” provides a clear warning that women’s suffrage would only serve to strengthen the political power of Mormons in Utah. Reflecting the racially-charged views of the time, the term “tribe” further cast Mormons as “un-American” and the embodiment of “The Other.”

Newspaper Article: “Minor Topics,” New York Times, December 17, 1867, 4.

This article was one of the early public statements suggesting that Utah would be a good place to experiment with female suffrage. Playing off of national anti-polygamy sentiment, the article pointed out that women were in the majority in Utah and might vote to end polygamy if enfranchised.

This article was one of the early public statements suggesting that Utah would be a good place to experiment with female suffrage. Playing off of national anti-polygamy sentiment, the article pointed out that women were in the majority in Utah and might vote to end polygamy if enfranchised.

Written Document: Draft of 1870 Utah Suffrage Clause

The handwritten draft of Utah’s 1870 suffrage bill shows some of the details that the legislature was considering in the early stages, including a lower voting age for women.

The handwritten draft of Utah’s 1870 suffrage bill shows some of the details that the legislature was considering in the early stages, including a lower voting age for women.

The final wording of the suffrage bill, approved on February 12, 1870, shows that the territorial legislature ultimately decided to keep the voting age 21 years old for both male and female voters.

Materials

Anti-Polygamy Legislation

When it became clear that Utah women would not use their voting rights to end polygamy, anti-polygamists throughout the nation lobbied U.S. Congress to pass laws pressuring the LDS Church to disavow polygamy. Several proposed anti-polygamy bills also included measures to revoke Utah women’s suffrage. Many Utah women opposed these bills by holding protest meetings and petitioning Congress not to disfranchise them. Still, Congress passed the Edmunds Act in 1882, revoking the political and voting rights of polygamists. When this legislation did not eradicate the practice of polygamy as hoped, Congress passed a stronger Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887. Part of this legislation took away the voting rights of all Utah women, whether they were Mormon or not, polygamous or monogamous, married or single. The withdrawal of the franchise that Utah women had exercised for seventeen years ignited many Utah women’s determination to regain the vote permanently with statehood.

Primary Source Set

“Open Letter to the Suffragists of the United States,” Anti-Polygamy Standard, March 1882

This open letter, unanimously adopted by the National Woman’s Anti-Polygamy Society, set forth the anti-polygamy arguments against women’s suffrage in Utah.

This open letter, unanimously adopted by the National Woman’s Anti-Polygamy Society, set forth the anti-polygamy arguments against women’s suffrage in Utah.

Political Cartoon: “The Mormon Question,” Daily Graphic, 1883

This political cartoon similarly contains commentary on the 1882 Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act. It depicts Uncle Sam in police uniform, wearing a sling with the label “Edmunds Law,” implying that the United States was in fact weakened, rather than strengthened, by the 1882 legislation. Uncle Sam stands at an open door, facing an armed Mormon man chained to three enslaved wives. The man is rolling up his sleeve and making a fist, threatening to strike Uncle Sam who has one of his hands tied. The three wives are portrayed as despairing, pleading for help, or too downtrodden to resist enslavement. The caption reads: “The Mormon Question: What is Uncle Sam Going to Do About It?” The cartoonist challenges Congress to go further than the Edmunds Act to combat the Mormon threat. It portrays suspicions that Mormons, like the Confederacy, were attempting to form their own sovereign country in the Mountain West to protect a way of life repugnant to the rest of the nation. Like other anti-Mormon propaganda of its time, this cartoon uses imagery of slavery, violence, and defiance against the nation to resonate with the deep fears of another insurrection in post-Civil War America.

This political cartoon similarly contains commentary on the 1882 Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act. It depicts Uncle Sam in police uniform, wearing a sling with the label “Edmunds Law,” implying that the United States was in fact weakened, rather than strengthened, by the 1882 legislation. Uncle Sam stands at an open door, facing an armed Mormon man chained to three enslaved wives. The man is rolling up his sleeve and making a fist, threatening to strike Uncle Sam who has one of his hands tied. The three wives are portrayed as despairing, pleading for help, or too downtrodden to resist enslavement. The caption reads: “The Mormon Question: What is Uncle Sam Going to Do About It?” The cartoonist challenges Congress to go further than the Edmunds Act to combat the Mormon threat. It portrays suspicions that Mormons, like the Confederacy, were attempting to form their own sovereign country in the Mountain West to protect a way of life repugnant to the rest of the nation. Like other anti-Mormon propaganda of its time, this cartoon uses imagery of slavery, violence, and defiance against the nation to resonate with the deep fears of another insurrection in post-Civil War America.

Written Document: Dr. Ellen Ferguson’s Speech from the Great Mass Meeting in Salt Lake Theatre, March 6, 1886

The “Great Mass Meeting” included speeches by Mormon women at the Salt Lake Theatre in 1886 in protest of what would become the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act. Dr. Ellen Ferguson was one of the many women who spoke.

Newspaper Article: “Honoring Edmunds,” Anti-Polygamy Standard, April 1882

This article provides a detailed explanation of the quilt made by the Woman’s Home Mission Society of the Ogden Methodist Church that was given to Mrs. Edmunds, wife of Senator Edmunds who sponsored the anti-polygamy legislation known as the Edmunds Bill of 1882 and the Edmunds-Tucker bill of 1887.

This article provides a detailed explanation of the quilt made by the Woman’s Home Mission Society of the Ogden Methodist Church that was given to Mrs. Edmunds, wife of Senator Edmunds who sponsored the anti-polygamy legislation known as the Edmunds Bill of 1882 and the Edmunds-Tucker bill of 1887.

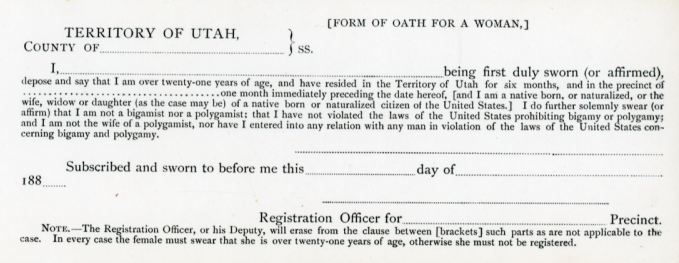

Artifact: Voter Registration Oath for Women in Utah Territory, 1882

This oath was required of women seeking to register to vote in the Territory of Utah following the Edmunds Act of 1882. A female voter was required to take an oath swearing that she not only met the voting requirements established in 1870 but also that she was not engaged in a polygamous relationship.

Materials

Territory / State Political Involvement

Once Utah women received the right to vote in 1870, they became politically active and exercised their newfound right in large numbers. Leaders of the Relief Society, the women’s organization of the LDS Church, immediately developed programs to educate women about the political process and civic engagement. The Woman’s Exponent carried political and suffrage news to women throughout Utah Territory. When the U.S. Congress disfranchised Utah women in 1887, formal suffrage activism within the territory became necessary. In 1889, Emily S. Richards led hundreds of women in organizing a Utah chapter of the National Woman Suffrage Association and began organizing local units throughout the territory, working through local Relief Societies. Within four months the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah had fourteen branches, and by February 1895, nineteen of Utah’s twenty-seven counties had suffrage organizations. Through these suffrage associations throughout the territory, Utah suffragists lobbied to regain women’s voting rights in Utah and supported the national suffrage movement. In 1895, Utah suffragists played a key role in successfully lobbying delegates to the constitutional convention to include women’s suffrage in the new state constitution, making Utah the third state in the nation where women could vote equally with men.

Primary Source Set

Newspaper Article: “Woman Suffrage Meeting: An Association for Utah,” Woman’s Exponent, Jan 15, 1889.

This article describes the January 10, 1889 meeting which officially organized the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah through the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). It includes details about the meeting, the officers elected, and the constitution of the organization.

Artifact: Banner for Utah Woman Suffrage Organization, 1893

Courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

The banner was used by the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah.

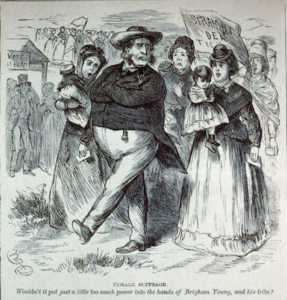

Artifact: Salt Lake County Woman Suffrage Association Membership Ticket, 1891

Courtesy of Ron Fox.

This is a photograph of Bathsheba W. Smith’s membership ticket for the Salt Lake County Woman Suffrage Association. It indicates that she paid her 50 cents in dues and was a card-carrying member of the suffrage organization.

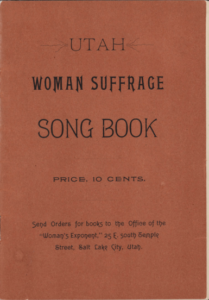

Artifact: Utah Woman Suffrage Songbook

This collection of nineteen songs related to freedom, equal rights, and suffrage was published and sold by the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah, with proceeds sent to Emmeline B. Wells at the Woman’s Exponent. The songs were sung at suffrage meetings and events.

Artifact: Woman Suffrage Association of Utah Stamp

This stamp maker, in the collection at the LDS Church History Museum, was used to stamp official documents and correspondence for the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah.

Materials

Emmeline B. Wells

No other Utah suffragist did more for the women’s suffrage cause than Emmeline B. Wells. An early advocate of women’s rights, she was the editor of the Woman’s Exponent from 1877 to 1914. Under her direction, the publication championed women’s economic, educational, and political rights in addition to sharing news about the LDS women’s Relief Society organization. After Wells led Utah women in sending long petitions to Washington D.C. for a constitutional women’s suffrage amendment, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony invited Wells to represent Utah and speak at the 1879 National Woman’s Suffrage Association convention in Washington. Outraged after losing the voting franchise in 1887, Wells led Utah’s suffragists in battling to regain the ballot. In January 1889, Wells helped found the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah and through it launched a campaign that succeeded in restoring the vote to Utah women in 1896. Shortly before Susan B. Anthony died, she had one of her gold rings sent to Wells as a token of their friendship. Wells and several other Utah suffragists continued working with the national suffrage movement even after Utah women regained the vote. The year before she died, Wells celebrated the victory of national women’s suffrage with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.

Primary Source Set

Photo: Emmeline B. Wells, January 14, 1879

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

This portrait of Emmeline B. Wells fittingly shows her sitting at her desk, where she spent much time as a poet, writer, journalist, and activist. It was taken during her tenure as the editor of the influential Woman’s Exponent.

Photo: Emmeline B. Wells, ca. 1915-1920

Courtesy of Ron Fox

This portrait of Emmeline B. Wells was taken during her time as general president of the Relief Society. She is seated at her desk, and several framed photographs of women are shown in the background.

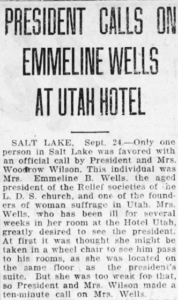

Newspaper Article: “President [Woodrow Wilson] Calls on Emmeline Wells at Utah Hotel,” Ogden Standard, September 24, 1919

This article described a personal visit made by United States President Woodrow Wilson to 91-year-old Emmeline B. Wells. It was an honor bestowed on Wells in recognition of her suffrage activism as well as her role in leading the wheat-saving program in Utah and then turning the grain over to the government during World War I.

This article described a personal visit made by United States President Woodrow Wilson to 91-year-old Emmeline B. Wells. It was an honor bestowed on Wells in recognition of her suffrage activism as well as her role in leading the wheat-saving program in Utah and then turning the grain over to the government during World War I.

“State’s Foremost Woman Dies,” The Salt Lake Telegram, April 25, 1921

“State’s Foremost Woman Dies,” The Salt Lake Telegram, April 25, 1921

This obituary, published on the day of her death, celebrated the many accomplishments of Emmeline B. Wells. It detailed her leadership in the suffrage movement, the National Council of Women, and the Relief Society as well as her influence as a writer, editor, and woman’s rights activist.

Materials

1895 State Constitutional Convention

Though Utah Territory had unsuccessfully applied for statehood several times over the previous four decades, the LDS Church’s disavowal of polygamy in 1890 increased Utah’s chances of being admitted to the Union as a state. In 1894, Congress passed the Enabling Act, which essentially invited Utah to apply again for statehood. At Utah’s 1895 Constitutional Convention, delegates (who legally had to be male) debated whether to include a clause in the state constitution that would grant Utah women the right to vote and hold public office. Delegate B. H. Roberts was one of the few who argued against the suffrage clause, but most of the delegates supported women’s suffrage (especially Franklin S. Richards). Backed by strong lobbying from female suffragists, the pro-suffrage delegates carried the day, and the clause for women’s suffrage was included in the proposed state constitution. Utah’s all-male electorate voted overwhelmingly to approve the constitution in November 1895, Congress ratified it, and President Grover Cleveland signed it on January 4, 1896. This made Utah the third state in the Union to grant equal suffrage to women. The people of Utah celebrated their long-awaited statehood as well as the re-enfranchisement of Utah women.

Primary Source Set

Photo: Convention Delegates, 1895

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

This photomontage includes images of the delegates and officers to the Utah State Constitutional Convention held on March 4, 1895. While women could not serve as delegates to this convention, two women were included as officers: Miss B.T. Macmasters and Miss Henrietta Clark, both serving as committee clerk.

“Convention and Woman Suffrage,” Woman’s Exponent, April 1, 1895

This article describes the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah convention that was held during the State Constitutional Convention. It includes the language of the memorial (petition) that the the suffragists presented to the delegates in favor of including women’s suffrage in the new state constitution.

Excerpt from B. H. Roberts’ State Constitutional Remarks, 1895

These excerpts are from B. H. Roberts’s speeches at the Utah State Constitutional Convention in 1895. Roberts was the key voice in opposing the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the state constitution.

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

Excerpt from Franklin S. Richards’s State Constitutional Remarks, 1895

These excerpts are from Franklin S. Richards’s speeches at the Utah State Constitutional Convention in 1895. Richards was the key voice in supporting the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the state constitution.

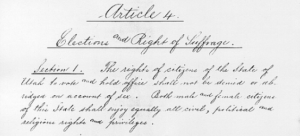

Suffrage Clause in Utah State Constitution

This original handwritten page of the Utah state constitution includes the suffrage clause guaranteeing that the right of suffrage and the right to hold office cannot be denied based on sex. It guarantees to male and female citizens equal civil, political, and religious rights.

Materials

1896 State Election

On November 3, 1896, the new state of Utah held its first general election, an election in which women could now vote again (after being disfranchised in 1887) and could also run for office for the first time. Voter turnout was high, with women voting in large numbers. Ten candidates (five Democrat and five Republican) ran for the five open state Senate seats, including three women: Martha Hughes Cannon as a Democrat, Emmeline B. Wells as a Republican, and Lucy A. Clark as a Republican. Cannon was elected as the first female state senator in the nation along with the rest of the Democratic ticket, defeating her husband Angus, who ran on the Republican ticket. Four women ran for election to the House of Representatives. Democrats Sarah E. Anderson of Weber County and Eurithe LaBarthe of Salt Lake County won election, while Republicans Martha Campbell of Salt Lake County and Mrs. F. E. Stewart of Utah County were defeated. At the county level, Margaret A. Caine was elected auditor of Salt Lake County, Ellen Jakeman was elected treasurer of Utah County, and eleven other women were elected as county recorders. W. W. Taylor, an African-American man, also ran for the state legislature as a Republican on an equal civil rights platform. Like nearly all of his fellow Republicans, Taylor did not win, but he did gain more than 6,500 votes, many more than the number of African-Americans in Salt Lake City. This was also the first election in which Utah, now a state, could vote for national offices such as president and vice-president. Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan won 82.7% of the Utah vote, but his opponent William McKinley ultimately won the presidency.

Primary Source Set

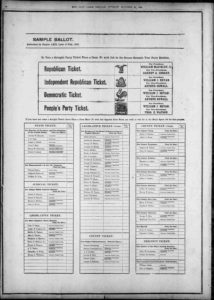

Artifact: “Sample Ballot,” The Salt Lake Herald, October 25, 1896

Courtesy of Ron Fox.

This sample ballot was published just prior to the 1896 election. It includes Emmeline B. Wells and Martha Hughes Cannon running for State Senate and Martha M. Campbell and Eurethe K. La Barthe running for the Utah House of Representatives.

Photo: Utah State Senate, 1897

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

This photograph of the first Utah State Senate was taken on the steps of the City and County Building in Salt Lake City. Martha Hughes Cannon, the first female state senator in the United States, is the woman on the left and the other two women are secretaries.

Materials

Martha Hughes Cannon

When Utah gained statehood in 1896 and the women of Utah regained the franchise, physician and suffragist Martha “Mattie” Hughes Cannon ran as a Democrat in an at-large election for one of five senate positions in the new state’s first legislature. Her husband, as well as Mattie’s friend and mentor Emmeline B. Wells, were also on the ballot as Republican candidates, but the Democrats swept the election. Mattie’s victory garnered national attention not only because she was the first woman elected to a state senate but also because she ran against and defeated her own husband. She served one four-year term with the otherwise all-male Utah Senate in the Salt Lake City and County Building. During her four years as a Utah state senator, Mattie continued to practice medicine and sponsored several legislative bills that revolutionized public health in Utah.

Primary Source Set

Photo: Martha Hughes Cannon and her daughter, 1899

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

This photograph shows Martha Hughes Cannon with her third child, “Mattie,” who was born during the end of her term as state senator.

Photo: Utah State Senate, 1897

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

This photograph of the Utah State Senate was taken on the steps of the City and County Building in Salt Lake City. Martha Hughes Cannon, the first female state senator in the United States, is the woman on the left and the other two women are secretaries.

The Salt Lake Herald, October 31, 1896

In responding to another newspaper’s endorsement of Angus Cannon for state senate, this article states: “Mrs. Mattie Hughes Cannon, his wife, is the better man of the two.” Martha Hughes Cannon went on to win the election over her husband and become the first female state senator.

Written Document: 1897 Legislative Bill for Utah School for the Deaf and Blind

Courtesy of Ron Fox.

This Senate bill, authored by Martha Hughes Cannon, authorized the building of a hospital for the State School for the Deaf and Dumb.

Written Documents: Martha Hughes Cannon’s Degrees and Certificates

Written Documents: Martha Hughes Cannon’s Degrees and Certificates

Martha Hughes Cannon earned four degrees. Included here are these diplomas, plus her certificate in elocution and her Certificate of Election to the Utah State Senate.

Materials

Susan B. Anthony's Utah Involvement

Susan B. Anthony is arguably America’s best-known suffragist, but her ties to Utah are lesser known. In 1871, the year after Utah women received voting rights, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited the territory and personally congratulated Utah for granting women the ballot. They held a five-hour meeting with three hundred local women in the Old Tabernacle, where the Salt Lake Assembly Hall now stands. Even though she opposed the Mormons’ practice of polygamy, Anthony staunchly supported Mormon women’s voting rights and invited Utah suffragists to participate in and even speak at national suffrage conventions. Anthony formed an enduring friendship with Utah’s leading suffragist, Emmeline B. Wells. After Congress revoked the voting rights of all Utah women through the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, Anthony mentored Utah suffragists on how to win those rights back. After Wells telegraphed Anthony to announce that Utah’s new state constitution would include women’s suffrage, Anthony quickly replied, “Hurrah for Utah, No. 3 State—that establishes a genuine ‘Republican Form of Government.’” She travelled to Utah to again personally congratulate Utah suffragists and to speak to a crowd of 6,000 in the Salt Lake Tabernacle during the 1895 Rocky Mountain suffrage convention. To show their appreciation for her ongoing support, women of Utah later sent Anthony a bolt of black silk produced in their woman-owned silk industry. Anthony had a cherished dress made from the silk, which today is displayed in her bedroom at the National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House in Rochester, New York. On the day of her death, she had one of her gold rings sent to Emmeline Wells in Utah, a symbol of her friendship and legacy.

Primary Source Set

Written Document: Letter from Susan B. Anthony to UWSA, July 1894, telling UWSA to ensure suffrage gets in state constitution: Exponent, August 1 & 15, 1894

This reprinted letter from Susan B. Anthony was addressed to the Utah Woman’s Suffrage Association upon the passage of the Enabling Act inviting Utah to apply for statehood. Anthony strongly advised the Utah suffragists to fight for women’s suffrage to be included in the new state constitution.

Photo: NAWSA Delegates at the Rocky Mountain Suffrage Association Conference, 1895

Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Photograph of national suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw with prominent Utah suffrage leaders such as Emmeline B. Wells, Martha Hughes Cannon, Sarah M. Kimball, Emily S. Richards, and others.

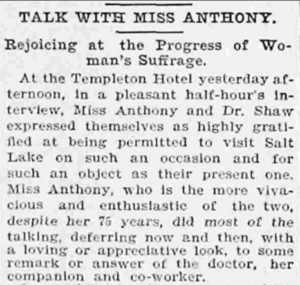

Newspaper Article: “Talk with Miss Anthony,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 13, 1895

Courtesy of Ron Fox.

This article describes an interview with prominent national suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Reverend Anna Howard Shaw in Salt Lake City. They visited Utah to personally congratulate the Utah suffragists on the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the proposed state constitution.

Newspaper Article: “Day of the Suffragists,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 13, 1895

This article, entitled “Day of the Suffragists,” describes the arrival of Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw in Salt Lake City for a convention of suffragists from the Rocky Mountain states. It provides detail on the sermon given by Reverend Shaw in the Tabernacle to an estimated 8000 as well as Susan B. Anthony’s congratulatory remarks regarding Utah’s statehood and equal suffrage.

Artifact: Susan B. Anthony’s Black Silk Dress

Photograph of a cherished dress owned by Susan B. Anthony. It was made from silk that was produced by Utah women and given to Anthony as a birthday gift from Utah suffragists.

Newspaper Article: Deseret Evening News, March 17, 1906

An article about the memorial service held in the Salt Lake City Assembly Hall upon the death of Susan B. Anthony. Suffragists such as Emily S. Richards, Emmeline B. Wells, Susa Young Gates, Alice Merrill Horne, Ruth M. Fox, and others commemorated the life and work of Susan B. Anthony and urged a continuing commitment to the suffrage cause that she held so dear.

Materials

Utah's Involvement in National Suffrage Campaign

When Utah gained statehood, only two other states (Wyoming and Colorado) allowed women to vote equally with men. Suffragists across the nation were still working toward a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. Leaders such as Emmeline B. Wells, Susa Young Gates, and Emily S. Richards continued to foster Utah’s relationship with national women’s organizations such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and the National Council of Women (of which the Relief Society was a founding member). In 1899, NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt visited Utah to establish the Utah Council of Women in place of the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah. Emmeline B. Wells was made a member of the national executive committee, and the newly-formed Utah Council of Women pledged to aid other states in their suffrage efforts. Utah women indeed continued to work with the national suffrage organization by providing funding, serving in leadership positions, hosting national leaders, and attending and speaking at national and international women’s rights conventions. Additionally, the national suffrage leaders held up Utah as an example of the success of women’s suffrage as they lobbied for a national amendment and in their state-by-state approach toward gaining suffrage. The continued involvement of Utah women in the movement, even after regaining their own suffrage, indicates their commitment to the cause of women’s suffrage itself. It demonstrates that for Utah’s women, support of suffrage was more than just a political maneuver to strengthen the LDS church, as some anti-suffragists and anti-polygamists had claimed.

Primary Source Set

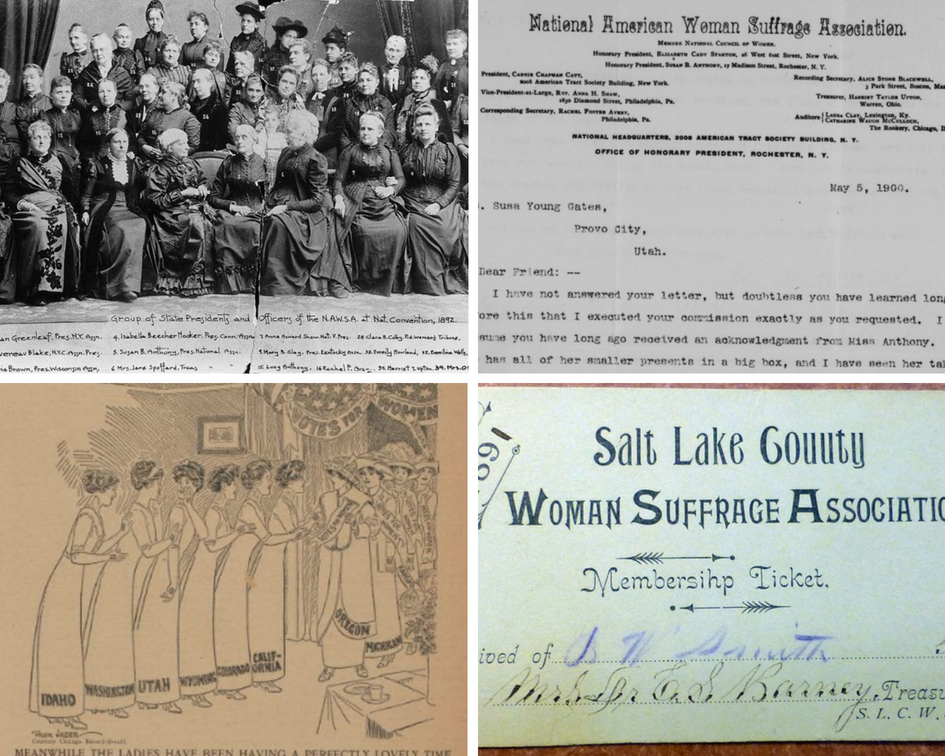

Photo: State Presidents and Officers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1892

Courtesy of Bryn Mawr Special Collections.

This photograph includes Emmeline B. Wells and Sarah M. Kimball, along with national suffrage leaders and presidents of other state suffrage associations, during the National American Woman Suffrage Convention in 1892.

Photo: Utah Delegates to the National Council of Women, 1899

Courtesy of LDS Church History Library.

This photomontage shows the delegates representing Utah at the 1899 triennial conference of the National Council of Women, including Emmeline B. Wells, Susa Young Gates, and Hannah Kaaepa.

Political Cartoon: “Conquerors,” Woman’s Journal, 1912

The cartoon depicts a suffrage parade, a bold tactic adopted by American suffragists beginning in 1910 to publicize their cause. This parade, however, is represented as a victory march featuring all the suffrage states in a procession of women on horses, casting aside opposing groups of onlookers labeled “Anti-Suffrage,” “Conservatism,” and “Prejudice.” In honor of its early enfranchisement of women, Utah is given a position of importance as one of the leaders of the suffrage procession. Portrayed as classically beautiful and clothed in the gown of a Greek goddess, the female representation of Utah is prominently placed on a white horse directly to the right of the leader. Other symbols include the laurel leaves worn by the central suffragist leading the procession, indicating victory, as well as the square graduation cap worn by the suffragist on the far left, symbolizing superiority, intelligence, and achievement.

Political Cartoon: “Meanwhile the ladies have been having a perfectly lovely time,” The Woman’s Journal, 1912

All traces of the former prejudice against Utah suffragists have disappeared, and Utah is portrayed as one of the dignified Western state hostesses welcoming the new wave of states into their suffrage tea party. With a friendly whisper between the portrayal of Washington State and the depiction of Utah, Utah is shown to be on friendly and equal footing with the other suffrage states. The caption reads: “Meanwhile the ladies have been having a perfectly lovely time.” The caption’s use of the word “ladies” to describe the women, including Utah suffragists, implies respectability and honor. It stands in stark contrast to the portrayals of Utah women in the late-nineteenth century anti-polygamy propaganda cartoons. The end of polygamy and Utah suffragists’ continued commitment to the national suffrage movement had by this time earned them an uncontested place of honor as one the original states to grant women’s suffrage.

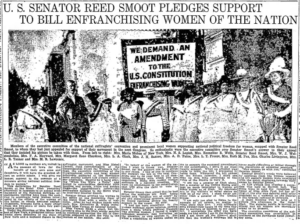

Newspaper Article: “U.S. Senator Reed Smoot Pledges Support to Bill Enfranchising Women of the Nation,” The Salt Lake Herald, August 20, 1915

Article describing Senator Reed Smoot’s support for a national women’s suffrage amendment and a mass meeting at the Hotel Utah with national leaders of the suffrage movement.

Photo: Utah Senator Reed Smoot and Suffragists, August 19, 1915

Courtesy of National Woman’s Party.

This photograph shows Senator Reed Smoot with prominent Utah suffragists, including Emmeline B. Wells, and members of the NAWSA executive committee in front of the Hotel Utah after he pledged support for the national suffrage cause.

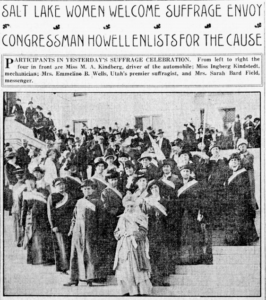

Newspaper Article: “Salt Lake Women Welcome National Suffrage Envoy,” Salt Lake Tribune, October 5, 1915

Article describing the suffrage celebrations that centered around the arrival in Salt Lake City of Sarah Bard Field and other national suffrage leaders from the Congressional Union of Women Voters.

Article describing the suffrage celebrations that centered around the arrival in Salt Lake City of Sarah Bard Field and other national suffrage leaders from the Congressional Union of Women Voters.

Photo: Suffrage Speech, Oct. 4, 1915

Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

This photograph shows national suffrage leader Sara Bard Field addressing women on the steps of the Utah State Capitol during a nationwide suffrage campaign. An elderly Emmeline B. Wells is standing on the platform behind Field with other state leaders.

Materials

Ratification of 19th Amendment

More than 70 years after the women’s rights movement began, Congress ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in August 1920. Utah ratified the amendment on October 2, 1919 during a special legislative session called expressly for that purpose. It was the seventeenth state, and the first of the original western suffrage states, to ratify the national suffrage amendment. Senator Elizabeth Hayward introduced the amendment to the Utah state senate for ratification, Representative Grace Stratton Airey moved for its adoption in the House, Representative Anna Piercey presided over the ratification in the House, and the other two female representatives gave brief addresses about the importance of women’s suffrage. The 19th Amendment officially became law upon ratification by the state of Tennessee. The amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” It important to note, however, that the 19th Amendment did not automatically grant suffrage to all women but rather removed gender restrictions from voting rights. Discriminatory citizenship laws as well as Jim Crow laws at the time still denied true suffrage rights to many minority women (and men) such as Native Americans, Asian-Americans, and African-Americans.

Primary Source Set

Written Document: Signed 19th Amendment Joint Resolution, May 19, 1919

The U.S. Senate and House of Representatives approved this joint resolution proposing a constitutional amendment extending the right of suffrage to women.

The U.S. Senate and House of Representatives approved this joint resolution proposing a constitutional amendment extending the right of suffrage to women.

Newspaper Article: “Equal Suffrage Measure is Adopted,” Salt Lake Herald, September 30, 1919

Newspaper Article: “Equal Suffrage Measure is Adopted,” Salt Lake Herald, September 30, 1919

This newspaper article reported Utah’s ratification of the 19th amendment by the Utah Legislature. Senator Elizabeth Hayward introduced the resolution and moved for ratification, which passed unanimously.

Artifact: The Suffrage Map Early in August 1920

This map shows the type of women’s suffrage permitted in each of the states in early August, 1920.

Photo: Tennessee Senate, August 1920

This is a photograph of the Tennessee Senate just after voting to ratify the 19th Amendment. Tennessee was the thirty-sixth state to ratify, making it the final state needed to reach the required three-fourths and officially make the suffrage amendment part of the Constitution.

This is a photograph of the Tennessee Senate just after voting to ratify the 19th Amendment. Tennessee was the thirty-sixth state to ratify, making it the final state needed to reach the required three-fourths and officially make the suffrage amendment part of the Constitution.

Newspaper Article: “Tennessee Votes Suffrage,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 18, 1920

This Utah news article reported the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Tennessee’s ratification meant that the required three-fourths of states had voted to grant suffrage to women through the constitutional amendment.

This Utah news article reported the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Tennessee’s ratification meant that the required three-fourths of states had voted to grant suffrage to women through the constitutional amendment.

Newspaper Article: “Suffrage Proclaimed,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 26, 1920

This article announced the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granting women the right to vote.

Newspaper Article: “Women Observe National Victory,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 1, 1920

This article describes a large celebration held in the hall of the Utah House of Representatives in honor of the ratification of the national suffrage amendment. The meeting and parade was organized by the Utah leaders of the National League of Women Voters and included speeches by Emmeline B. Wells, Emily S. Richards, and other local suffrage and political leaders.

Materials

Utah Women Shaping the State

While testifying before Congress in 1898, Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon declared: “The story of the struggle for woman’s suffrage in Utah is the story of all efforts for the advancement and betterment of humanity.” Like Martha, thousands of women from all communities in Utah participated in this suffrage story and shaped the new state at the turn of the twentieth century.

These women and many others used their voices to make their communities stronger during Utah’s early years of statehood. Their legacy of leadership continues today as we build upon their trailblazing work to create better days in the future.

Primary Source Set

Newspaper Article: Elizabeth Taylor’s Speech at the “Western Federation of Colored Women” convention, 6 July 1904

Elizabeth Taylor founded an organization called the “Western Federation of Colored Women” and hosted a convention in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1904. In her opening speech at the convention, she reminded Black women from across the western states why they needed to work together to uplift their communities. The WFCW was part of a club movement and blossomed in the 1890s and 1900s under the umbrella of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs as Black women organized to address discrimination, lynching, and other difficulties facing their families and communities.

Elizabeth Taylor founded an organization called the “Western Federation of Colored Women” and hosted a convention in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1904. In her opening speech at the convention, she reminded Black women from across the western states why they needed to work together to uplift their communities. The WFCW was part of a club movement and blossomed in the 1890s and 1900s under the umbrella of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs as Black women organized to address discrimination, lynching, and other difficulties facing their families and communities.

Newspaper Article: Hannah Kaaepa’s Advocacy for Hawaiian Women’s Voting Rights

Minute Book: Lucy Heppler’s Leadership in the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah

Diary: Emmeline B. Wells Working for Women’s Equal Representation

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience