Additional Resources

The Hello Girls,

Emelia Lumpert and Mary Marshall

1917 – 1918

“Both Salt Lake girls keenly desired to do something to help win the war.”

by Rebekah Clark

Better Days Historical Director

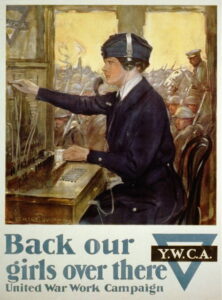

Recognizing a dire need for better communications as World War 1 continued to rage, the U.S. War Department issued an urgent request for trained female telephone operators who were fluent in French. Two Utah women, Emilia Lumpert and Mary Marshall, made history as they answered that call and joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps in 1918 to become “soldiers of the switchboard.”[1] This elite group of 223 women, often nicknamed the “Hello Girls,”[2] faced grueling hours and dangerous conditions near the battlefields in France. Their expertise and bravery enabled crucial Army communications and expedited the success of the Allied Forces.

Millie Lumpert, c. 1911

Emelia Katharine Lumpert, sometimes called Millie, was born in St. Gallen, Switzerland on October 26, 1892 to Emil Lumpert and Maria Kleber. She immigrated to Salt Lake City with a friend in 1914 on the ship Scharnhorst.[3] Before she ever dreamed of heading to the battlefront, Millie was busy graduating high school from Weber Academy (now Weber State University), singing soprano in the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, and working as a dental assistant and then as a telephone operator at Salt Lake City’s Walker Bank.[4]

Mary Marshall

Mary Marshall, on the other hand, was a society girl from a prominent Salt Lake family. Her father, Utah’s U.S. District Judge John Augustin Marshall, was the nephew of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, and her mother, Jessie Kirkpatrick, was the daughter of a distinguished pioneer lawyer. Mary was born in Utah on January 19, 1890, and was raised Catholic in a predominantly Latter-day Saint community. From a well-educated family, she studied in Berlin, Germany from 1909-1910 when she was around twenty years old. She also made a name for herself by winning the intermountain women’s tennis championship in 1912 and 1916.[5]

Despite their different backgrounds, these intrepid women found common ground in their immediate desire to serve their country during the war. Recognizing the benefit that their ability to speak fluent French offered, both Millie and Mary applied in December 1917 in response to General Pershing’s call for bilingual telephone operators to join the American Expeditionary Forces. They underwent strict training at the Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Co., including physical tests, psychological evaluations, French language exams, and loyalty investigations by secret service agents. This process was likely even more rigorous for Millie, who was not yet an American citizen. On December 18, 1917, she filed a Declaration of Intent for Naturalization, which included an oath swearing that she was not an anarchist and renouncing all allegiance to Switzerland.[6]

Women working the switchboards at Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company in SLC, 13 August 1915. Notice the “cooling machine” at right: a block of ice and electric fan. Used by permission, Utah Historical Society.

By the start of the First World War, the telephone had become the fastest way to communicate, making it one of the most important war technologies and aptly nicknamed the “nerves of the army.”[7] The telephone was a fairly new invention that couldn’t function without a series of operators plugging cords into switchboards until they reached the correct location. When the U.S. entered the war, their ally, France, had already been fighting for a long time. Their telephone system and all its wires had been destroyed. The United States had to start from scratch.

Because most switchboard work was done by women back home, most American soldiers had no experience. They couldn’t run the telephone operations quickly enough, and they couldn’t communicate with their allies in French. Over 7600 women applied when the Army first sent out its call for help. The 223 women who were ultimately selected to join the Army Signal Corps were highly skilled. They could connect calls five times more quickly than the soldiers had, with one captain estimating that each woman could connect 300 calls an hour.[8] Such efficiency and speed mattered in battle communications when seconds could mean the difference between life and death.

Fourth Unit of the U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators in New York City on June 13, 1918. Mary Marshall is top row, fifth from left and Emilia Lumpert is front row, sixth from right.

Millie and Mary left Salt Lake City on February 28, 1918 to join the fourth unit of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. They served under the leadership of Chief Operator Geneva Mildred Marsh. After several months of training at the army training center in Trenton, New Jersey, the unit went to New York City to prepare for their departure. On one of their final days there, they rode “flag-draped automobiles” and “paraded up Broadway behind the New York 12th Infantry, and stopped at Times Square, where [they] sold $6,000 worth of [Liberty Loan] bonds.”[9] The fourth unit left New York harbor on June 28 and crossed the torpedo-infested Atlantic to France.[10] They were issued army dog tags and gas masks on their first day. Their work for the war had begun.

The Signal Corps operators were stationed throughout France, at times “upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself.”[11] Some were so close to the front lines that they had to work with helmets and gas masks within reach. The first unit of switchboard operators experienced an air raid on their building on their very first night: one operator remembered sliding down the hotel bannister in her nightgown to the underground shelter. Operators were not only responsible for fielding calls and translating at an unrelenting pace but also for communicating confidential information using military codes.

As the first women serving in the Army, they faced gender barriers and blazed the path for future female enlistment. Several women were assigned to train male soldiers to help work the switchboards. One operator remembered some soldiers treating her disrespectfully, but they changed their attitudes when she reminded them that, “any soldier could carry a gun, but the safety of a whole division might depend on the switchboard.”[12] By the end of the war, they had earned the respect and gratitude of all the soldiers they served and helped expand the nation’s cultural assumptions about women’s role.

After the war, the Army Signal Corps operators were all required to stay overseas longer than many of the soldiers because communications were needed to establish the fragile peace agreements. Mary had studied in Germany just a few years before, but she returned under very different circumstances when she was assigned as a telephone operator with the American Expeditionary Force during the first advance on the Rhine in November 1918, just after the Armistice.[13] Because of her knowledge of German as well as French, she was stationed in Coblenz, Germany for more than three months and then transferred back to duty in Paris.

After the war, the Army Signal Corps operators were all required to stay overseas longer than many of the soldiers because communications were needed to establish the fragile peace agreements. Mary had studied in Germany just a few years before, but she returned under very different circumstances when she was assigned as a telephone operator with the American Expeditionary Force during the first advance on the Rhine in November 1918, just after the Armistice.[13] Because of her knowledge of German as well as French, she was stationed in Coblenz, Germany for more than three months and then transferred back to duty in Paris.

Millie Lumpert also appears to have continued her telephone operating service in Germany with the American Expeditionary Forces during the initial occupation.[14] After her release from duty, she officially finalized her naturalization and became a U.S. citizen on October 4, 1920.[15] She settled in Washington D.C., where she managed the foreign language department of National Geographic and traveled to France several more times in the following years. Millie married Colonel William G. Powell in 1928 at the age of 35.[16] She passed away in 1986.

Mary Marshall returned to Salt Lake City in July 1919. She briefly resumed playing tennis and won a state championship meet later that year. She also spoke about her service overseas, including a speech at the Utah War Mothers association conference in August 1919.[17] The next May, she married Howard W. Fitch. Maud Fitch, another Utah woman who had served bravely in France as an ambulance driver, was Howard’s sister and Mary’s bridesmaid. Mary and Howard lived in Eureka, Utah in Juab County, had three children, and later moved to California.

The 223 women of the Army Signal Corps in WW1 were the first women to wear U.S. army uniforms. They received equal pay as the male soldiers of comparable rank, wore dog tags and rank insignia, swore the army oath, were subject to court marshall, and were consistently told that they were in the army. But when they returned from overseas, the United States Government declared that legally they were civilian contractors and denied them veteran benefits. After decades of advocacy, the surviving operators were finally granted veteran status in 1977, just one year after Mary Marshall passed away.

The Hutchings Museum in Lehi, Utah and the U.S. World War One Centennial Commission are now advocating for Emelia Lumpert, Mary Marshall, and the other “Hello Girls” to be honored with the Congressional Gold Medal – an effort that you can join here! The contributions of these “switchboard soldiers” left a lasting impact on the nation and the world.

Quotation source: “Misses Marshall and Lumpert Given Active Roles in America’s War Cause,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, February 28, 1918.

[1] “Brave Girl Soldiers of the Switchboard,” The Sun [New York], 29 Sept. 1918, available at Chronicling America, LOC.

[2] “U.S. Women in War Protest ‘Hello Girls,’” Salt Lake Herald-Republican 8 September 1918, p. 13; Jill Frahm, “The Hello Girls: Women Telephone Operators with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 3, no. 3 (July 2004): 271–93.

[3] “Misses Marshall and Lumpert Given Active Roles in America’s War Cause,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, February 28, 1918; New York U.S. Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1820-1957, Emilie Lumpert, January 3, 1914.

[4] “City to Join in Hymns of Praise Proclaiming the Christ Child,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, December 24, 1916; “Local Girl on Way Overseas to Operate Phones,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 10, 1918.

[5] “Miss Mary Marshall Wins Intermountain Title,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, September 3, 1912, p.8; “Miss Marshall Singles Champ,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, September 4, 1916, p. 6.

[6] Emelia Katherine Lumpert, in Utah, U.S., Naturalization and Citizenship Records, 1858-1959, at ancestry.com.

[7] “Girls Do Good Work: American Telephone Operators Now Serving in France,” Bourbon News [Kentucky] 16 July 1918, p 6.

[8] Captain E. J. Wesson,“Girls Do Good Work: American Telephone Operators Now Serving in France,” Bourbon News [Kentucky] 16 July 1918, p 6.

[9] “Pioneers in Service Telephone Operators Taking Their Place in the Service of Uncle Sam Overseas,” in The Telephone Review, Vol. 9, No. 7, July 1918, pp. 203-206.

[10] U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists, June 28, 1918, available at ancestry.com.

[11] President Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Record, 65th Cong., 2d sess. (GPO, 1918), 10928-10929.

[12] Merle Egan Memoir, 38, quoted in Elizabeth Cobbs, The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 2017), 161.

[13] “Utahn at Coblenz Writes: Meets Other Salt Lakers,” Salt Lake Tribune , June 13, 1919, p. 8.

[14] Emelia C. Lumpert, Emergency Passport Application, December 30, 1918, available at ancestry.com.

[15] New York, U.S. Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, Emelia Cathrine Lumpert, November 15, 1922, available at ancestry.com.

[16] “Military Officer Weds Salt Lake Girl,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 9, 1928, p. 63.

[17] “Semi-Pro and Amateur Notes,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 14, 1919, p. 11; “Utah War Mothers to Cooperate with Legion,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 4, 1919, p. 3.