Gertrude Lancaster,

Amity among Black Women

1892 – 1979

“We must unite still more strongly.”

By Rebekah Clark and Lauren Webb

As president of the Western Federation of Colored Women and an active participant in Utah’s Black churches and clubs, Gertrude Stevens Lancaster strengthened her community through social organization and service during World War I.[1]

Gertrude Stevens was born in 1892 in Salt Lake City. Her parents were both born in Virginia, most likely to enslaved or formerly enslaved families. Gertrude was actively involved in Salt Lake’s Black community starting from a young age. She walked in the Emancipation Day Parade when she was only nine years old.[2] At her eighth grade graduation, she recited the poem, “The Present Crisis,” which was written as an abolitionist protest.[3] In 1912, she married Mack Lancaster in Salt Lake City and they had two daughters. Gertrude attended Calvary Baptist Church as well as its sister-congregation, Trinity African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.), where she spoke at events and served as the organist.[4]

Congregation at Calvary Baptist Church, 1920s. Used by permission, University of Utah Marriott Library.

At the time, these two churches in Salt Lake served not only as sites of worship but also as social centers for the Black community. Like many other churches, Calvary Baptist and Trinity A.M.E. were associated with service clubs that provided organized opportunities for women to contribute to their communities. Gertrude’s church, for example, organized what was called the Booker T. Washington War Savings Association during World War I. The United States government had created stamps to sell to raise money for the war effort. Members of Gertrude’s congregation went door-to-door selling the stamps and hosted patriotic events at the church to encourage others to participate in the organization.[5]

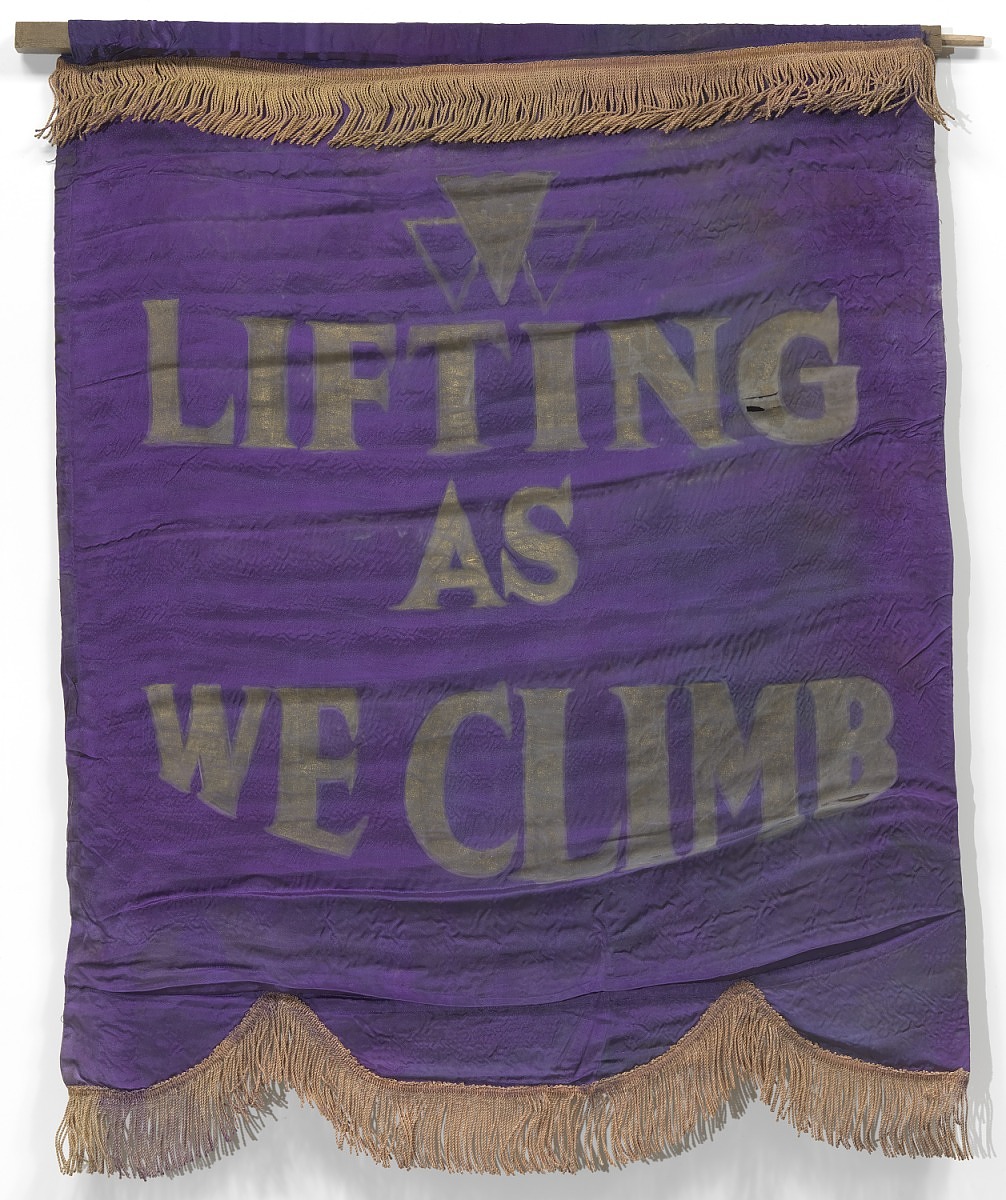

Many clubs were specifically for women. Gertrude Stevens Lancaster served as the vice president and then as the Utah state president of the Western Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, a coalition founded in 1904 by Elizabeth Taylor that officially organized Black women’s local clubs into a cooperative group. As part of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, they adopted the motto “Lifting As We Climb.” Significantly, in 1918 Gertrude represented this organization at a large meeting of the Utah State Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense. She reported that there were 250 Black women in Salt Lake engaged in wartime charity efforts.[6]

One organization represented by the Western Federation of Colored Women and led by Gertrude was the Amity unit of the Red Cross.[7] This segregated group of women met once a week at one of the member’s homes to knit and sew supplies for soldiers.[8] They were sometimes given space at the Red Cross building to use the sewing machines if they weren’t being used by white women.[9] Many Amity women had husbands overseas and were raising kids as single parents. They made home-related decisions with the war in mind, including participating in boycotts of certain foods. Milk and eggs were expensive, and women chose to go without so that those foods could go to soldiers instead.[10] The Amity unit participated in the large Red Cross fund parade in 1918, where they helped gather donations from the crowd on a huge American flag.[11]

Amity, a word denoting friendship, was a fitting name for the organization and for Gertrude’s work. Women’s clubs made it possible for women like Gertrude Stevens Lancaster to find friendship and community in a place with relatively few Black residents. This friendship empowered women to be actively involved in Utah’s public sphere. In 1921, at a convention of the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs over which she presided, Gertrude recited the organization’s accomplishments and declared: “We colored women of Utah and Idaho have much of which to be proud.” She then laid out her “aspirations for the future,” urging: “We must unite still more strongly, for better homes, better citizens, equal rights.”[12]

A few years after the war ended, Gertrude divorced and moved to California with her two daughters, Edna and Isabel. She worked as a nurse and married Robert Johnson in 1929. Gertrude continued to be a leader among women in Black congregations in California. Soon after she became the president of the Women’s Council of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Oakland, a newspaper complimented her “upon the deep interest she has aroused in the women of her church in so short a time.”[13] She also became the director of the church’s youth choir. Gertrude Lancaster continued to work for unity and amity in her community throughout her life.

[1] During the early 1900s, use of the term “colored” when referring to African Americans was considered standard and neutral language, but the term is now widely understood to be offensive.

[2] “Emancipation Day,” Deseret Evening News, September 24, 1901, p. 2.

[3] “Eighth Grade Pupils of the Public Schools to Graduate Tonight,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 31, 1906, p. 3.

[4] “Liberated Remember Martyred Liberator,” Salt Lake Telegram, February 13, 1909, p. 4, “Colored Church Meetings,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, February 20, 1908, p. 10.

[5] “Employees Aiding in Stamp Drive,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 30, 1918, p. 3.

[6] “Women’s Council Committee Meets,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 9, 1918, p. 20, “Colored Women in State Convention in Ogden,” Ogden Daily Standard, June 7, 1919, p. 12.

[7] “Gauze Workers Busy Everywhere in Country, Army of Loyal Women Making Many Dressings,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 8, 1918, p. 14. In addition to Gertrude, Amity members included at least Anna McMillan, Mary Johnson, Etta Quinn, Mattie Hatfield, Bessie Roundtree, and Eleanore McQuir. “More Clothing is Required at Once,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 15, 1918, p. 14.

[8] “Children’s Chorus to Wind up Drive,” Salt Lake Telegram, December 24, 1917, p. 2.

[9] “Inquiry Made into Letter Sent by Committee,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, April 25, 1918, p. 3.

[10] “S.L. Colored Women Decide to Ban All Hi Cost Products,” Salt Lake Telegram, December 15, 1916, p. 10.

[11] “Salt Lake Cheers and Chuckles over Parade,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 1, 1918, p. 8.

[12] “Colored Women of Utah Hold Their Convention,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 12, 1921, p. 35.

[13] “Local,” Oakland Tribune, vol. 119, no. 161, December 10, 1933, p. 18.