Suffrage Colors Explained

by Katherine Kitterman, BD2020 Historical Director

July 10, 2020

Woman Suffrage Badge, National Museum of American History.

You’ve seen the photos of sash-wearing suffragists holding banners outside the White House or marching down Pennsylvania Avenue. But do you know the meaning of the colors they wore? And what about the colors of other important organizations working for women’s rights?

The first major campaign for women’s suffrage in the U.S. was an 1867 referendum in Kansas, and that’s where suffragists . During that campaign, suffragists like Susan B. used the sunflower, which was the Kansas state flower, as a symbol of their cause.[1] Yellow flowers and yellow ribbons became emblematic of the women’s rights movement and agitation for the vote.

In the 1890s, Utah suffragists often wore yellow flowers or ribbons at their rallies and decorated with yellow for suffrage events. For example, in an American Fork suffrage rally in 1892, “the ladies wore the yellow ribbon and quite a number of gentlemen were adorned with sunflowers.”[2] When national suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw visited Utah in 1895, yellow décor was used for a reception in their honor.[3]

When Utah women first served in the legislature, they also used yellow flowers as a symbol of the power of women’s votes. Family legend holds that Alice Merrill Horne and Martha Hughes Cannon sprinkled petals on male legislators’ desks ahead of votes on the bills they sponsored on education and public health.

Suffrage flag, National Museum of American History.

In the early 20th century, suffrage leader Alice Paul understood the importance of creating an iconic visual theme to promote the cause of votes for women. When she formed the National Woman’s Party (NWP), she borrowed the color scheme used by British suffragettes. While the British movement used green, white, and violet (for give women the vote), Paul substituted gold for green to continue the American suffrage tradition. Whether marching in parades or silently picketing the White House, suffragists began carrying purple, white, and gold banners and wearing the now-iconic sashes.

A 1913 article in The Suffragist explained, “Purple is the color of loyalty, constancy to purpose, unswerving steadfastness to a cause. White, the emblem of purity, symbolizes the quality of our purpose; and gold, the color of light and life, is as the torch that guides our purpose, pure and unswerving.”[4] Suffragists wore white for several reasons. It made them stand out, but it was also a claim to moral purity against the anti-suffragist arguments that only ‘unnatural’ or morally depraved women wanted the vote.

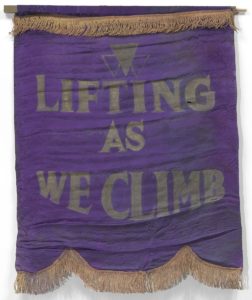

Oklahoma Federation of Colored Womens Clubs banner, National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Purple and white were also the colors of the National Association of Colored Women, which formed in 1896 to promote equality for Black women. National suffrage organizations often excluded Black women from their ranks (formally or informally), and also often sidelined Black women’s concerns. In the NACW, black women worked for a wide variety of reforms including women’s suffrage, but also focusing on anti-lynching, expanding educational opportunity, and fighting voter suppression and white supremacy in the South. Local clubs affiliated with the NACW often marched in parades and held public events displaying their own banners and signs. They used purple as a symbol of royalty, and white for purity.[5]

To commemorate the centennial of the 19th Amendment on August 26, 2020, buildings across Utah and the United States will be lit in purple and gold. These colors pay homage to the the NWP colors and slogan, “Forward out of Darkness, Forward into Light.” But they can also remind us of the millions of women of color who continued the struggle for equal suffrage past 1920. For more information about how to join in lighting a building or home in Utah, visit www.utahheritage.org.

[1] https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_507974

[2] ”A Grand Woman Suffrage Rally,” Woman’s Exponent, August 15, 1892, p. 4.

[3] “Notable Assemblage,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, May 13, 1895, p. 5.

[4] The Suffragist, December 6, 1913.

[5] “National Association of Colored Women,” National Women’s History Museum.