UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Abolition: The Catalyst for the Women’s Rights Movement

Abolition: The Catalyst for the Women’s Rights Movement

Lesson Overview

This lesson examines the beginnings of the women’s suffrage movement as an outgrowth of the abolitionist movement. Students will learn about key figures who were involved in both movements and analyze primary source documents to compare abolitionist and women’s suffrage arguments. Utah history connections are provided by students examining the rights of Utah women in the 19th century in comparison to women in the East. Students will learn about how social movements spark new movements and how arguments made for and against the expansion of rights are similar regardless of time period.

Recommended Instructional Time: 1-2 class sessions

Historical Background for Educators

Although the constitution of the new United States did not give women the right to vote, a concept of “republican motherhood” developed in the young country that made some space for women’s involvement in public life. As America industrialized and expanded westward in the early 1800s, many people described life in terms of “separate spheres” for men and women–where men went out into the world to participate in economic and political life while women’s energy and effort was focused domestically, caring for home and family. However, political and intellectual leaders often spoke of the importance of raising and educating informed and moral citizens in the young American republic. This duty, called “republican motherhood,” recognized women’s role in promoting public virtue and political stability and acknowledged that they, through their children and family, played an important part in American public life.

Drawing on this concept of republican motherhood, many American women expanded women’s traditional “sphere” through their participation in charitable organizations and reform movements. This extended women’s traditional moral and domestic authority into public life more directly than before as they worked together to clean up cities and towns, alleviate poverty, and support laws and regulations to protect the morality of society. The first time American women spoke out nationally on a political issue was in the early 1830s, when women across the country petitioned against President Andrew Jackson’s policy to remove Native Americans in the southern U.S. to the western side of the Mississippi. Although women’s petitions were unsuccessful in changing the President’s plans, they did succeed in convincing many Americans that women’s duty to guard the nation’s moral virtue obligated them to speak publicly on some political issues, such as the treatment of a vulnerable population.

“I ask no favors for my sex. I surrender not our claim to equality. All I ask of our brethren is, that they will take their feet from off our necks.” –Sarah Grimké, letter, July 17, 1837

Some women soon extended this justification for women’s political involvement to advocacy to end slavery, which many considered to be an inhumane and sinful practice. Angelina and Sarah Grimké, Lucretia Mott, and others began speaking publicly for anti-slavery organizations before mixed crowds of men and women, even though they were mocked and threatened for doing something considered so unladylike. Thousands more women wrote articles for abolitionist newspapers, signed anti-slavery petitions, and circulated anti-slavery literature. Still, women who joined the cause of abolition found that traditional assumptions and attitudes about women often limited the scope of their participation and leadership in the movement. When the American Anti-Slavery Society was founded by William Lloyd Garrison in 1833, women were not allowed to be delegates. This led Lucretia Mott and several other white and African-American women to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society later that same year. In this organization, women conducted meetings, ran petition campaigns, and directed fundraisers, as well as speaking publicly. Still, female abolitionists faced discrimination not only from slavery supporters but also from within their own movement. This highlighted to them the injustice of women’s inferior legal and social standing. When women were not allowed to speak or be seated at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had both travelled to attend the convention, began discussing what needed to be done for women’s rights.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” —Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

Eight years later, in 1848, Mott, Stanton, and others gathered at Seneca Falls, New York for the first-ever women’s rights convention. There, they discussed Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments, which detailed the injustice of laws and customs that made married women legal non-entities with no property rights or rights to their children, prevented women from pursuing education and many means of employment, and barred them from voting for lawmakers whose decisions affected every aspect of their lives. The Declaration affirmed that women were men’s natural equals and resolved that women should seek the right to vote as a means to remedy many of the injustices they faced. This resolution in favor of women’s suffrage was hotly debated at the convention, and only ratified after the prominent abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass spoke in its favor, supporting Stanton’s reasoning that the women not only had a natural right to the vote, but that it would be the best tool to improve their legal and social subordination.

“There are many rights which woman should possess yet of which she is denied by custom and by statute law, but more especially by the former.” –Emmeline B. Wells, Woman’s Exponent, June 1872

In many ways, women’s involvement in the anti-slavery cause had given them both the skills and the justification for a sustained campaign to improve women’s rights. The anti-slavery movement had given them a platform for public speaking and opportunities to develop the organizational skills they needed to launch a movement. It had also opened their eyes to the injustices women faced as they began to see some similarities between their legal subordination and that of enslaved people. As they encountered barriers and faced opposition to their public involvement on behalf of enslaved workers, many abolitionist women found a voice–and a reason–to speak up in their own behalf.

Slavery was legal in Utah Territory, but the practice was never very widespread. There were likely fewer than 50 enslaved people living in Utah when Congress abolished slavery in all U.S. territories in 1862. Because Utah never developed an abolition movement, there wasn’t the same connection between abolition and women’s rights activism in Utah that there was in eastern states. By contrast, most white Utah women became involved in the women’s rights movement when their own civil and religious rights were threatened by outside legislation that sought to disfranchise them after they began voting in 1870.

Artist unknown, “An Unsightly Object—Who Will Take the Axe and Hew It Down?”, The Judge, 1882

However, the Republican Party considered slavery and polygamy (the latter practiced in Utah) to be “twin relics of barbarism.” After the adoption of the 14th Amendment abolished slavery in 1868, many Americans turned their attention to eradicating polygamy. United States President Chester Arthur responded to these concerns by condemning polygamy in each of his State of the Union addresses and calling upon Congress for more radical legislation. Political cartoons during this time often depicted polygamous Utah women as slaves, trying to draw similarities between the two practices. Anti-polygamists argued that polygamous women were oppressed and that providing them with voting rights would help liberate them (much like the arguments surrounding support for the 15th Amendment, which enfranchised black men). The desire to end polygamy would prove to be a strong motivator for many to support Utah women’s suffrage in 1870, but after Utah women had been voting for years and polygamy was still practiced, antipolygamists supported revoking women’s voting rights through Congressional legislation in 1887.

Key Utah State Standards Addressed

Social Studies

Content Standards

- U.S. II Standard 2.1: Students will use primary and secondary sources to identify and explain the conditions that led to the rise of reform movements, such as organized labor, suffrage, and temperance.

- U.S. II Standard 2.3: Students will evaluate the methods reformers used to bring about change, such as imagery, unions, associations, writings, ballot initiatives, recalls, and referendums.

Literacy in Social Studies Standards

- Reading for Literacy Standard 1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- Reading for Literacy Standard 2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- Reading for Literacy Standard 7: Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- Writing for Literacy Standard 7: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to analyze primary source documents to determine the arguments made by abolitionists and suffragists.

- Students will be able to compose a compare/contrast written piece comparing the arguments made by key abolitionists and early suffragists.

Guiding Questions

- Who were the key figures in both the abolitionist and suffrage movements? Why did many abolitionists become suffragists?

- What were the similarities and differences between the two movements?

- What were the arguments for first focusing on voting rights for African-American men before the voting rights of women?

- How did the rights of Utah women compare to the rights of other American women?

Vocabulary

(noun) the legal ending of slavery

Many people worked for the abolition of slaves.

(noun) a person who supported the ending of slavery in the United States

Angelina Grimke and Sojourner Truth were abolitionists who fought to end slavery.

(verb) to free a person from someone else’s power

Anti-polygamists wanted to emancipate women in polygamous marriages.

(n) the right to vote

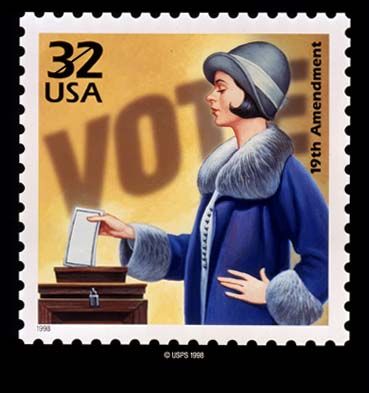

The 19th Amendment granted the franchise to women.

(v) to give the right to vote

The 19th Amendment franchised women.

(noun) A marriage system in which a person is married to more than one person at a time.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints practiced polygamy, in which some husbands had more than one living wife.

(noun) The right to vote in a political election

During the women’s suffrage movement, women fought for and won the right to vote in political elections.

(noun) a person who worked to get voting rights for women

Suffragists fought for women’s voting rights.

Materials Needed

Building & Activating Background Knowledge

Lesson

Building and Activating Background Knowledge

- The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 is considered the start of the women’s rights movement. Show students the following video to provide information about this historic convention: History Channel’s “What Happened at the Seneca Falls Convention?” (4:27)

- Questions to Consider:

- What was the impetus for (or cause of) the Seneca Falls Convention?

- What was the result of this convention?

- Questions to Consider:

- Provide students with a copy of excerpts from the Declaration of Sentiments (1848). Have students examine this document, paying particular attention to the list of grievances beginning with “He has never permitted…” You may choose to have students begin the document at this point. Refer to this article for an outline of (the lack of) women’s rights detailed in the document.

- What rights (or lack of rights) did women have in the early 1800s?

- What stands out to them about this list? What do they notice?

- What questions do they have?

- Have students compare this list with the handout “Timeline of Women’s Rights in Utah (1847-1896).” Utah was actually quite progressive with women’s rights during the establishment of the Utah Territory and statehood, particularly in comparison with states in the East.

- You may have students also look at the editorial from the Woman’s Exponent and/or consider the political cartoons that depicted polygamous Utah women as slaves. How do these cartoons contrast with the rights granted to Utah women?

- Review key vocabulary.

Analyzing Primary Source Documents

There were many people who played a part in both the abolitionist and suffrage movements. Below are several key people involved in both movements. Have students learn about these individuals and read their respective writings. You may decide to divide students into groups and assign the pairs of historical individuals to each group. Or you may have students work in partners or individually.

The Grimké Sisters and the Forten Sisters

Angelina Grimké’s “Address to the Massachusetts Legislature” (1838)

Sarah Forten Purvis’s poem, “The Slave Girl’s Address to Her Mother” in Liberator (January 29, 1831)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s “Speech to the Anniversary of the American Anti-Slavery Society” (May 8, 1860)

Lucy Stone’s “Disappointment is the Lot of Women” (1855)

Sojourner Truth and Susan B. Anthony

Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” (1851)

Susan B. Anthony’s “Make the Slave’s Case our Own” (1859)

Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison

Frederick Douglass’s North Star editorial (1848)

William Lloyd Garrison’s “No Compromise with the Evil of Slavery” (1854)

- First, have students research about their assigned people via the Internet and use the first page of “Comparing Historical Figures” worksheet to guide this research. Consider how these people compare. Note that the second page may be used as an assessment option.

- Then, have students examine the primary-source documents written by these people. Use the “Analyzing Written Documents” handout from National Archives. What additional insights do they gain about these historic people? Have students pay particular attention to the arguments made in support of abolition and women’s rights.

- Use the “Comparing Abolition & Women’s Suffrage Arguments” organizer to help students consider the commonalities of arguments between abolitionists and women’s rights advocates. What arguments are made for African-American rights and women’s rights? What arguments did proponents of both movements give? What differences?

Assessment

- Option A: Have students compose a summary paragraph about how these two movements compare and influence each other. Students may also write this paragraph as an argument, explaining if they find these reformers’ arguments convincing or not. They should use evidence to support their opinions.

- Option B: Have students develop a comic strip depicting a conversation between the two historical figures they researched–a template can be found on page two of the “Comparing Historical Figures” worksheet. What would these historical figures say to the other? This comic strip should depict the views of the historical figures on women’s rights and abolition.

Adaptations

- Have students learn about these individuals in groups or partners, and then, as a class examine two of the key primary-source documents as a class, focusing especially on Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments (1848) and Garrison’s “No Compromise with the Evil of Slavery” (1854).

- Provide information about the key players to students and move directly to the primary source documents.

- Provide a short excerpt from each of the primary-source documents instead of having students read the documents in their entirety.

- Focus on only two of the key individuals–one from the abolitionist movement and the second from the women’s rights movement–and identify the arguments from both movements together.

Extensions

- Examine the history of voting rights of women in Utah, particularly noting how voting rights were taken away from polygamous men and all women in the Utah Territory in 1887 with the Edmunds-Tucker Act.

- Utah women were also writing about women’s rights. Compare the arguments made by women’s rights advocates in the East with women in Utah by examining an editorial called “Woman’s Rights and Wrongs” in the first issue of the Woman’s Exponent in June 1872 written by Utah’s leading suffragist, Emmeline B. Wells.

- Further questions for students to consider and explore: How do the arguments made by abolitionists and suffragists compare to activists of other progressive and civil rights movements? How do the arguments of these early women’s rights advocates compare to the arguments made by today’s women’s rights advocates? Do you think that women in the United States have all of the rights that Stanton asked for in the Declaration of Sentiments? Why or why not? Use evidence to support answers.

- During this time period, the Republican party considered slavery and polygamy to be the “twin relics of barbarism” and worked to abolish both practices. Anti-polygamists focused their energy on the Utah Territory. Compare arguments of abolitionists, suffragists, and anti-polygamists. What arguments do you find the most compelling or persuasive?

- Examine political cartoons regarding slavery and women’s rights of this time period. How do they reflect the views of these abolitionist and women’s rights activists–and those who opposed these views? In particular, examine the political cartoons depicting polygamous Mormon women.

- At many times in U.S. history, Americans have portrayed newcomers or immigrants or minorities as different from (and therefore inferior to) “American” culture and practices in ways that were dangerous to the rest of the nation. For example, Irish immigrants were portrayed as dirty and diseased, Native Americans as violent and uncivilized, African-Americans as unintelligent, etc. These portrayals highlighted supposed physical and racial differences to support the arguments that these minority groups were not capable of participating in politics and government because they weren’t “white” or “American” enough. For example, University of Utah professor, W. Paul Reeve, writes, “Outsiders suggested that Mormons were physically different and racially more similar to marginalized groups than they were to white people. Mormons were conflated with nearly every other ‘problem’ group in the nineteenth century — blacks, Indians, immigrants, and Chinese — a way to color them less white by association.” Have students examine how these issues played out in the history of voting rights in Utah and in regards to minority voting rights in Utah and nationally. Additionally, how do these issues play out today?

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience