UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Examining (and Debating) Women’s Suffrage Arguments and Memorabilia

Examining (and Debating) Women’s Suffrage Arguments and Memorabilia

Lesson Overview

This lesson begins with an overview of the national women’s suffrage movement through a picture book read-aloud: Miss Paul and the President: The Creative Campaign for Women’s Right to Vote (or through an alternative voting simulation. Then, students will analyze primary source documents and suffrage memorabilia to identify arguments made by the anti-suffrage and pro-suffrage sides. Students will create their own pro- or anti-suffrage items.Students will consider how they can personally affect change and improve their communities. Teachers may choose to extend the lesson by staging a women’s suffrage debate or rally.

This lesson is also available on Canvas Commons.

Recommended Instructional Time: 30-90 minutes

Historical Background for Educators

When the United States Constitution went into effect in 1789, it allowed states to regulate their own voting laws. Even though the new country was founded on the ideals of liberty and equality, most states only allowed white male landowners to vote. Out of the original thirteen states, New Jersey was the only one to enfranchise citizens without limitations based on gender or race, so long as they met the property-holding requirements. The property requirements meant that most black men and married women were unable to vote, but some single and widowed women could–and did–vote in the state’s early elections. However, in 1807, New Jersey restricted voting rights to white male citizens who paid taxes. Although women in some states were able to vote in school board elections in rural areas, women did not legally vote in state- or territory-wide elections again until Utah women voted in 1870.

“I recognize no rights but human rights — I know nothing of men’s rights and women’s rights.” –Angelina Grimké, 1837

This didn’t mean, however, that American women weren’t involved in politics at all. Many women used their moral authority to expand their traditional domestic roles as wives and mothers into public life, working to protect the helpless and clean up public morality. As they formed women’s organizations to fight slavery, many women began speaking up in behalf of their own rights as women through public speaking, petitioning, and lobbying elected officials. After the Civil War, two national suffrage associations worked for women’s suffrage with a state-by-state approach (the American Woman Suffrage Association) and one focused on a national constitutional amendment (the National Woman Suffrage Association). Other suffrage organizations formed later in the more than 70-year movement for women’s voting rights, including the National Council of Women Voters, National Woman’s Party, and National Association of Colored Women. There were also powerful anti-suffrage organizations, where women argued that women didn’t want or need the vote, and that it would degrade women to bring them into men’s dirty world of politics.

In Utah, the territorial legislature passed women’s suffrage in 1870 and women citizens voted for 17 years before the U.S. Congress passed a law revoking their voting rights in 1887. Utah women soon joined with the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) since this national organization allowed polygamous women to join (the AWSA did not), and Utah women formed the affiliated Utah Woman Suffrage Association in 1889 and organized chapters throughout the Territory. Utah suffragists wrote newspaper articles, gave speeches, and signed petitions asking for women’s suffrage in Utah and in the rest of the country. Due to their efforts, when Utah became a state in 1896, its state constitution granted women equal political rights with men to vote and hold office.

“This great work can never be done by one half of the human family; it is the opinion of all who think deeply that men and women must do the work together, and unitedly.” –Emmeline B. Wells

Although support for women’s suffrage was much higher in Utah than in the rest of the nation, the arguments put forward by Utahns both for and against women’s suffrage were very similar to those articulated by suffragists and anti-suffragists across the country. In the 1800s, many Americans, both men and women, believed that women simply weren’t “fit” for the duties of citizenship such as voting and jury duty because of their supposed physical, intellectual, and emotional weakness. Arguments against women’s suffrage all the way up through 1920 often emphasized women’s domestic duties to home and family. These arguments sometimes suggested that women already had a say in politics through their influence on their husbands and sons, or they reasoned that women were too busy with their domestic responsibilities to get involved. They also claimed that women’s inherent purity and morality would be damaged by political involvement. On the other hand, suffragists argued that women and mothers had the same, if not a greater, stake in society because they were most closely connected with the interests of the next generation. Suffragists also used arguments grounded in natural and human rights to argue for women’s natural equality with men and against the injustice of denying the vote to women when they were affected by the laws made by elected officials.

“The life of the average woman is not so ordered as to give her first hand knowledge of those things which are the essentials of sound government…She is worthily employed in other departments of life, and the vote will not help her fulfill her obligations therein.” –Josephine Jewell Dodge, President of National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, May 1915

Suffrage organizations produced political imagery in cartoons, posters, and advertisements, trying to create a space in the public consciousness for women’s political culture. These images highlighted the desirability and importance of women’s involvement in political decision-making and made the case that women were very capable of improving American society through politics. Many images implied that women’s special qualities (and motherhood) made them the kind of voters who would clean up the problems in American society and put public interests first. Suffrage imagery directed at less conservative audiences often emphasized equality, freedom, and empowerment for women.

“To me, it was shocking that a government of men could look with such extreme contempt on a movement that was asking nothing except such a simple little thing as the right to vote.” –Alice Paul, 1974

Alice Paul headed a newer, more radical wing of the suffrage movement that employed public spectacle to advance the cause. Born into a Quaker family, Paul sometimes attended suffrage meetings with her mother, Tacie Parry Paul. Alice studied in England as a young woman, where she got involved with the suffrage movement there. She was introduced to British suffragists’ methods of civil disobedience and was arrested three times. Back in the U.S., Alice joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and soon headed its Washington, D.C. chapter. She organized NAWSA’s suffrage parade in D.C. in 1913 but soon split from the organization due to disagreements over strategy and tactics as NAWSA favored more traditional methods of lobbying lawmakers. Alice founded the Congressional Union in 1913 (later the National Woman’s Party in 1916) and began to employ some of the more militant tactics she had learned in England, including the first ever picketing of the White House with signs accusing President Wilson of hypocrisy in promoting democracy abroad while denying voting rights to women at home. Two women from Utah, Minnie Quay and Lovern Robertson, were among the 165 women who were arrested for doing so, and their poor treatment in prison (including force feeding when some of the women staged a hunger strike) forced President Wilson to order that they be released and garnered national attention and sympathy for the suffrage cause. Alice Paul’s more radical strategies played a large role in gaining support for women’s suffrage across the nation. Under her leadership, the NWP adopted an iconic visual theme with purple, white, and gold flags, banners, and sashes.

The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, was a big step toward political equality for American women because it prohibited any state from denying voting rights on the basis of sex. Still, just like Utah’s suffrage law, this only applied to citizens of the United States–that meant Native American and Asian immigrant women had no legal right to vote because they were not considered citizens under current U.S. law. Women of color faced voting discrimination and intimidation, especially in southern states. There was still more work to be done to gain citizenship and voting rights for all American women.

Key Utah State Standards Addressed

Social Studies

- Standard 3: Students will understand the rights and responsibilities guaranteed in the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

- Objective 2: Assess how the US Constitution has been amended and interpreted over time, and the impact these amendments have had on the rights and responsibilities of citizens of the United States.

- Standard 5: Students will address the causes, consequences and implications of the emergence of the United States as a world power.

- Objective 2: Assess the impact of social and political movements in recent United States history.

English Language Arts

- Reading: Informational Text Standard 7: Draw on information from multiple print or digital sources, demonstrating the ability to locate an answer to a question quickly or to solve a problem efficiently.

- Reading: Informational Text Standard 9: Integrate information from several texts on the same topic in order to write or speak about the subject knowledgeably.

- Writing Standard 1: Write opinion pieces on topics or texts, supporting a point of view with reasons and information.

Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to analyze primary-source documents to determine pro- and/or anti-suffrage arguments.

- Students will be able to create an anti- or pro-suffrage document (i.e. a poster or flyer, a pin, a banner, a postcard, a short speech or petition) and (possibly) participate in a debate.

Guiding Questions

- Why is voting important?

- How has the Constitution been amended to grant voting rights to various groups of people?

- What tactics and strategies are employed by those involved in social movements like the women’s suffrage movement?

- What impact did the women’s suffrage movement have on the United States?

- What role did Utah play in the national women’s suffrage movement?

- Why did some people support women’s suffrage? Why did others not support women’s suffrage?

- Why are voting rights denied of certain groups? Why were women denied voting rights?

- How did race play a part in the women’s suffrage movement and the ratification of the 19th Amendment?

Vocabulary

(noun) a change in the words or meaning of a law or document (such as a constitution)

The 19th Amendment in the U.S. Constitution grants women voting rights.

(noun) a ticket or piece of paper used to vote

Seraph Young was the first woman in the modern United States to cast a ballot in an election.

(noun) a series of events designed to influence voters in an election

Suffragists like Susan B. Anthony led the campaign for women’s voting rights.

(verb) to take part in a series of events to influence voters

Suffragists campaigned for women’s voting rights.

(noun) a representative who votes on behalf of others

Susa Young Gates was one of many delegates representing the women of Utah at national suffrage conventions.

(verb): to try to influence government officials to make decisions for or against something.

Anti-polygamists lobbied Congress to make polygamy illegal.

(noun) a written document that people sign to show that they want a person or organization to do or change something

Suffragists wrote petitions to convince lawmakers to pass a women’s suffrage amendment.

(verb) to ask a person, group, or organization for something in a formal way

Anti-polygamists petitioned Congress to pass anti-polygamy legislation.

(verb) to make official by voting for and signing (a constitutional amendment)

In August 1920, the 19th Amendment granting women’s voting rights was ratified by three-fourths of the states.

(noun) The right to vote in a political election

During the women’s suffrage movement, women fought for and won the right to vote in political elections.

(noun) a person who worked to get voting rights for women

Suffragists fought for women’s voting rights.

Materials Needed

Lesson

Options for Activating and Building Background Knowledge

- Option A: Read aloud to the class: Miss Paul and the President: The Creative Campaign for Women’s Right to Vote by Dean Robbins, Illustrated by Nancy Zhang.

-

- Book overview from Amazon: “When Alice Paul was a child, she saw her father go off to vote while her mother had to stay home. But why should that be? So Alice studied the Constitution and knew that the laws needed to change. But who would change them? She would! In her signature purple hat, Alice organized parades and wrote letters and protested outside the White House. She even met with President Woodrow Wilson, who told her there were more important issues to worry about than women voting. But nothing was more important to Alice. So she kept at it, and soon President Wilson was persuaded.”

- Possible discussion questions either as a whole class or in pairs:

- Why weren’t women allowed to vote?

- Why did women want the right to vote?

- What things did Alice Paul do to fight for women’s rights? Were they successful? Why do you think so?

- How do you think women felt as they worked to gain voting rights but it took decades for that to happen? How do you think they felt once the 19th Amendment was ratified?

-

- Option B: If you do not have access to the picture book, have students participate in a voting simulation (provided) to get an understanding that at one point in our U.S. history, women (and other groups) were not allowed to vote. You may choose to use the same discussion questions as above.

Then, for all:

- You may want to review “key vocabulary” and use the website timeline on the home page to point out key suffrage events and dates that happened nationally and in Utah.

- The following images can be found in the Powerpoint. Show the political cartoon, “The Awakening.” Discuss that while the women’s rights and suffrage movement got its start in the East, it was the western territories and states that led the way in passing legislation that gave women voting rights.

- Show photo of Utah suffragists with Senator Smoot outside Hotel Utah. Ask students what they notice in this photograph. Explain that Utahns were leaders in and very involved in the women’s suffrage movement. To learn more, read “Receiving, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote: The Story of Utah Women’s Suffrage” or watch the short video (2:51) about this history.

- Show 1920 map of women’s suffrage. What do students notice about this map? What stands out to them? For example, Utah was the second Territory to grant women’s voting rights (1870) and the third state to grant these rights (1896). Women in Utah were the first women to vote in the modern United States on February 14, 1870. But these voting rights were taken away by U.S. Congress in 1887. Utah women worked with national leaders to get their voting rights back and did so when Utah was granted statehood in 1896. Suffragists in each territory/state worked with national leaders (like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul) and national organizations. You may want to ask students to compare this map to “The Awakening.”

- You may also want to show students historic photos of Alice Paul and the events depicted in the picture book.

Analyzing Primary Source Documents

- Students will examine primary source documents to determine arguments made by suffragists and anti-suffragists: What reasons did suffragists have for wanting voting rights? Why did anti-suffragists oppose women’s suffrage? Have students examine the primary source documents looking for these reasons. Note: You may choose for sake of time to only focus on the pro-suffrage arguments, particularly if you are not choosing to do the optional debate/rally.

- Divide students into groups of 4. Provide each group with examples of postcards, a song/poem, and a short speech from the pro-suffrage side or anti-suffrage side. These artifacts can also be found in the Powerpoint. You may also choose to do this activity as a gallery stroll, posting these artifacts on the walls around the room and letting students browse them.

- Using the graphic organizer, ask students to identify the reasons provided in these documents for granting or not granting women’s suffrage. What arguments did they make? What symbols, colors, images did each side use to convey their messages? How did they try to convince voters/legislators? Do students think these tactics were convincing?

- Guide a class discussion. What questions do these primary sources raise for students? Discuss with the class the reasons given by pro and anti-suffrage groups. Write these reasons on the board and have them also write the reasons they did not already identify down on their organizer. You may want to compare the reasons they listed to the reasons listed in the provided “cheat sheet” chart.

- Explain to students that these debates about women’s suffrage went on for decades until 1919 when Congress finally voted “yes” on what would become the 19th Amendment. Even though Utah had granted women suffrage in 1896 with statehood, many Utahns still worked towards a national women’s suffrage amendment.

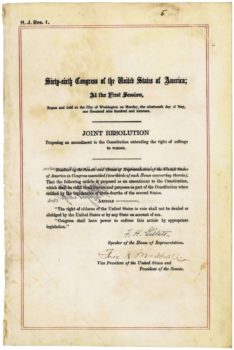

- Show text of the 19th Amendment to students. Show timeline (or map) of when states ratified the 19th Amendment (make sure to point out Utah and remind students that Utah had granted voting rights in 1870 [50 years before nation] and 1896 [24 years before nation]).

- The 19th Amendment was eventually ratified on August 26, 1920 after Tennessee became the 36th state to pass it. Show photos of 19th Amendment vote in Tennessee, the front page of the Salt Lake Telegram, and women celebrating the Amendment’s ratification. For more background info, read the Smithsonian Magazine’s “How Tennessee Became the Final Battleground in the Fight for Suffrage.”

- Make sure to point out that the 19th Amendment only granted voting rights to citizens. There were still groups who were in the United States who were not considered citizens at this time and could not vote (i.e. Native Americans, Asian Americans) and that some states put restrictions on voting to make it so African Americans could not vote–even though they were citizens. So even though this legislation passed and the Constitution was amended, groups continued to fight for citizenship, voting rights, and an end to lynching and voter restriction laws.

Assessment

- Students will then create pro- or anti-suffrage items to highlight the arguments made by these sides. You may decide how many items you’d like them to create. They can select to create a poster or flyer, a pin, a banner, a postcard, a short speech or petition using the primary sources as models. Have them explain their reasons for why they created their pro or anti-suffrage item(s) in the way that they did. Why did they use that particular imagery? Or colors? Or slogan?

- (optional) Organize a pro/anti-suffrage debate or rally with students using the items they created and the speeches/petitions they wrote as props/platforms for their arguments.

Adaptations

- Have students work in partners rather than in groups as they examine primary source documents.

- As a class, examine the primary sources together, modeling to students how to read these documents.

- Decide to have all students look at only one side (pro or anti-suffrage), discuss, and then, examine the documents representing the other side.

- Adapt the number of items–and the types of items–students produce.

- Have students verbally explain their rationales for the suffrage items they created to a partner rather than providing a written response.

Extensions

- Have students identify and learn more about the Utah women who were involved in the movement nationally from the “Key Players” page.

- Have students share why the women’s suffrage movement has meaning and importance to them today. Does it matter to them that Utah was a leader in the suffrage movement? Why or why not? Why does it matter if women vote?

- Learn more about groups who did not have voting rights with the passage of the 19th Amendment and/or who were barred from voting due to voter suppression laws and practices. What might those who were involved in fighting for these rights say to those who fought for women’s voting rights during the women’s suffrage movement?

- Women in the United States and in Utah have been civically-minded and engaged for a long time–voting in elections, running for political office, petitioning for causes, and leading various political and community organizations. How does this involvement in the past compare with involvement by women nationally today? And in Utah?

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience