UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Advocates for Change: Comparing Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, and Emmeline B. Wells

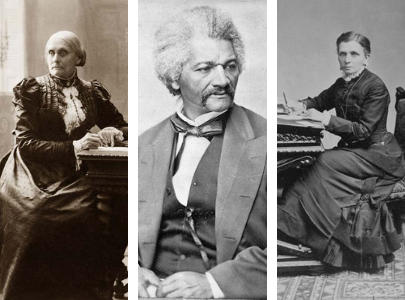

Advocates for Change: Comparing Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, and Emmeline B. Wells

Lesson Overview

Through a whole-class read-aloud of the historical fiction picture book (text provided), Friends for Freedom: The Story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass, and two historical articles, students will compare activists Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, and Utahn Emmeline B. Wells. Students will examine the statue that depicts the friendship of Anthony and Douglass and complete one of the following: a) a compare/contrast essay, b) a sketch of a statue to represent the friendship between Anthony and Wells, or c) a dialogue between Anthony, Douglass, and Wells. The purpose of this lesson is to not only learn about these advocates for change, but to develop the skills of civil and respectful dialogue, particularly with those with whom we may disagree.

This lesson is also available on Canvas Commons.

Recommended Instructional Time: 30-90 minutes

Historical Background for Educators

The American abolition movement was connected in many ways to the movement for women’s rights and suffrage. The women’s rights movement was born in upstate New York, a hotbed of anti-slavery activity, and many leaders of the women’s rights movement first became involved in public life through their work to end slavery. Some abolitionists supported the struggle for women’s rights as well, including Frederick Douglass, the most famous spokesperson for the abolition movement. He and Susan B. Anthony became friends as they worked to support the same causes from their homes in Rochester, New York.

“Many Abolitionists have yet to learn the ABC of woman’s rights.” –Susan B. Anthony, June 1860

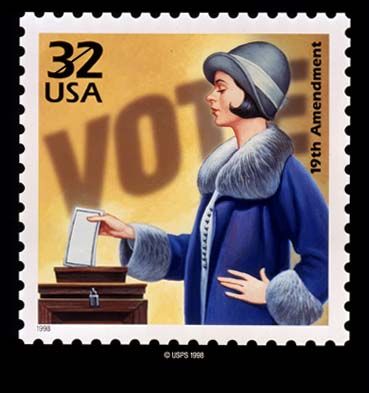

Susan B. Anthony was born in 1820 and raised in a Quaker family with a reforming spirit. A teacher for many year, Anthony became involved with the temperance but wasn’t permitted to speak at temperance rallies because she was a woman. This experience and her work speaking for the American Anti-Slavery Society convinced her that women needed the right to vote in order to be able to influence public affairs. When women were not enfranchised along with black men after the Civil War with the 15th Amendment, Anthony dedicated her life to women’s suffrage organizations campaigning for a constitutional amendment to secure women’s suffrage. She founded and led the National Woman Suffrage Association (later the National American Woman Suffrage Association), went on speaking tours throughout the country, gathered petitions, and spoke before every Congress from 1869 to 1906 to ask for a national amendment. Anthony’s commitment to the principle of equal suffrage was unshakable–unlike most other national suffrage leaders, she didn’t let her opposition to the Mormon practice of polygamy keep her from supporting Utah women’s voting rights. In thanks for her support, Utah women sent Anthony a bolt of black silk they had produced as a present for her 80th birthday in 1900, which she made into a cherished dress that is now displayed in her bedroom in Rochester. Anthony’s tireless work for women’s suffrage wasn’t realized until 14 years after her death in 1906, when the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment” was ratified in 1920. Anthony’s 200th birthday fell in the year 2020, which was also the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment.

“Woman, however, like the colored man, will never be taken by her brother and lifted to a position. What she desires, she must fight for.” –Frederick Douglass, July 1848

Frederick Douglass became a close friend of Susan B. Anthony through their work together for the abolition and women’s rights movements. Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on a Maryland plantation in 1818. He learned to read and write while working as an enslaved ship carpenter in Baltimore and later escaped slavery and lived in Massachusetts. Douglass began to speak publicly about his life in slavery and the evils of the practice, and William Lloyd Garrison soon invited him to lecture across the North on behalf of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass eventually settled in Rochester, New York, near many other abolitionists, and published a newspaper called the Northern Star. In addition to his anti-slavery work, Douglass was also involved with the women’s rights movement. He attended the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention and forcefully encouraged other attendees to support the call for women’s right to vote included in the Declaration of Sentiments. During the Civil War, he recruited African-American troops and lobbied the government for their fair treatment. After the war, Douglass founded the American Equal Rights Association with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to push for universal suffrage (both for African-Americans and for all women). Douglass split with these women over his support for the 15th amendment, which enfranchised black men but not women, but they later reconciled and worked together again. Douglass continued to support the cause of women’s suffrage until his death in 1895.

“I desire to do all in my power to help elevate the condition of my people, especially women.” –Emmeline B. Wells, personal diary, January 4, 1878

Emmeline B. Wells was a Utah woman who worked for decades to promote women’s rights. She first met Susan B. Anthony when Anthony visited Utah in 1871 to celebrate Utah women gaining suffrage, and Wells slowly built a friendship with the leader of the national women’s movement as she attended several national suffrage conventions. Anthony visited Utah again in 1895 to celebrate the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the proposed state constitution, and she even bequeathed a gold ring to Wells when she died in 1906. Wells was the editor of the women’s newspaper called the Woman’s Exponent for almost 40 years from 1877 to 1914, printing information about advancements for women across the country and around the globe as well as representing Mormon women’s views and faith. Wells’s editorials supporting women’s voting rights, educational rights, and economic rights were emphatic, passionate, and widely read. The offices for the Exponent became Utah’s de facto suffrage headquarters where local and visiting suffragists gathered to share information and strategize. As Utah’s best-known suffragist, Wells helped to coordinate Utah women’s efforts with those of national organizations like Anthony’s NWSA in support of a national constitutional amendment. Wells was a member of numerous women’s organizations and in 1910 became the president of the Relief Society, an independent women’s organization affiliated with the Mormon church and dedicated to charitable service. Under her direction, Mormon women stored wheat which they sold to the U.S. government during World War One. Wells lived to see the 19th amendment ratified and died one year later at the age of 93.

Key Utah State Standards Addressed

Social Studies

- Standard 5: Students will address the causes, consequences and implications of the emergence of the United States as a world power.

- Objective 2: Assess the impact of social and political movements in recent United States history.

English Language Arts

- Reading: Literature Standard 3: Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or drama, drawing on specific details in the text (e.g., how characters interact).

- Writing Standard 9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

Learning Objectives

- Students will compare and contrast Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, and Emmeline B. Wells by reading a historical fiction picture book and two informational articles.

- Students will develop a statue sketch using the statue of Anthony and Douglass as a model and provide rationale for their sketch using evidence from the readings. OR students will compose a compare/contrast essay.

Guiding Questions

- How did individuals work together within social and political movements to make changes?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of working with others on causes?

- How do the arguments for abolition and suffrage compare?

- How can we disagree with others in civil and respectful ways?

Vocabulary

(noun) the legal ending of slavery

Many people worked for the abolition of slaves.

(noun) a person who supported the ending of slavery in the United States

Angelina Grimke and Sojourner Truth were abolitionists who fought to end slavery.

(noun) a person who works for a cause or group

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were advocates of women’s suffrage.

(verb) to support or argue for a cause or policy

(verb) to free a person from someone else’s power

Anti-polygamists wanted to emancipate women in polygamous marriages.

(n) the right to vote

The 19th Amendment granted the franchise to women.

(v) to give the right to vote

The 19th Amendment franchised women.

(noun) The right to vote in a political election

During the women’s suffrage movement, women fought for and won the right to vote in political elections.

(noun) a person who worked to get voting rights for women

Suffragists fought for women’s voting rights.

Materials Needed

Lesson

Activating Background Knowledge

- Ask students to individually consider if they agree or disagree with a set of statements about friendship. Then, have students share their answers with a partner and explain their answers.

- Explain that today they will learn about two unlikely friendships: 1) between Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass who both worked for blacks’ freedom and rights and women’s rights, and 2) between Susan B. Anthony and Utahn Emmeline B. Wells who both worked for women’s rights.

Working with Historical Fiction

- Read aloud to the class, Friends for Freedom: The Story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass by Suzanne Slade, Illustrated by Nicole Tadgell. You can also use the video of a read-aloud (16:59) in order to freely access the book.

- Book overview from Amazon: “No one thought Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass would ever become friends. The former slave and the outspoken woman came from two different worlds. But they shared deep-seated beliefs in equality and the need to fight for it. Despite naysayers, hecklers, and even arsonists, Susan and Frederick became fast friends and worked together to change America.”

- Ask students to consider how Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass were both alike and different. Provide students with the compare/contrast chart to complete during the read-aloud (you may choose to stop after reading certain sections for them to write down) or have them complete it after the read-aloud either independently or with a partner.

- Make sure to share the two author’s notes with students as it provides additional historical information and insight.

- Additional questions for students to consider:

- Why do you think Susan and Frederick’s friendship was able to survive their differences?

- How did they support each other?

- What lasting contributions did Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass make to life in the United States today?

- What are the similarities and differences between fighting for slaves’ rights and women’s rights?

- Have students look again at their responses to the friendship statements now that they have learned about the Anthony/Douglass friendship. Do they still agree/disagree with the same statements? Are there any they would change? Why or why not?

- Display the photo of the statue of Susan and Frederick and/or show the 360-degree video of the statue. Ask students: Do they think the statue represents Susan and Frederick well? Do they think it depicts their friendship and personalities well? Why or why not? If they could add something to the statue, what would they add? And why?

- Pair students. Assign one student to read about Susan B. Anthony’s work in Utah and her friendship with Emmeline B. Wells. Have the other student read about Emmeline B. Wells and her advocacy work nationally and in Utah.

- Then, have the students share the information from their assigned articles with their partners. You may also decide to have pairs read both articles.

- Ask students to consider the following questions:

- What additional information did they learn about Susan B. Anthony? How does this compare to what they already knew or learned about her? How does it compare to Frederick Douglass? Add this information to their compare/contrast charts.

- How does Emmeline B. Wells compare to Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass? Add this information to their compare/contrast chart.

- What lasting contributions did Anthony and Wells make in Utah and nationally that we still see today?

- Why are Anthony, Douglass, and Wells considered “advocates for change”? What advocates for change do students see today? How can students be advocates for change in their communities?

- Have students look again at their responses to the friendship statements now that they have learned about the Anthony/Wells friendship. Do they still agree/disagree with the same statements? Are there any they would change? Why or why not?

Assessment

- Three options:

- Option A: Students write a compare/contrast piece that explains the similarities and differences between at least two of the three people they read about–Anthony, Douglass, or Wells. They need to use evidence to support their claims.

- Option B: Have students write a dialogue between Anthony, Douglass, and Wells. What would they discuss? What would they agree and disagree about? Make sure this dialogue includes both their similarities and differences.

- Option C: Create a sketch of a statue representing the friendship of Anthony and Wells. Use the statue of Anthony and Douglass as a model. The design should highlight the similarities and differences between the two women. Students should provide a short written explanation providing justification for their choices in concept and design.

Adaptations

- Choose to focus on only two individuals rather than three for comparison.

- Read the short articles about Anthony and Wells as a class.

- Explain the statue that students may create in writing rather than sketching it.

- Provide individual copies of the picture book to students so they can follow along.

- Provide students with sentence frames or a template to write the compare/contrast piece, i.e. “Anthony and Douglass are similar because…” “Wells is different from Anthony because…” “One way Douglass and Wells differ is…”

Extensions

- African-American women fought for their rights during the abolitionist movement, and later, also during the suffrage movement. Learn about these women like Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Terrell, and more. Consider how they compare to Anthony, Douglass, and Wells. You may also choose to compare women involved in the Civil Rights movement: i.e. Rosa Parks, Ella Baker, Coretta Scott King, Ruby Bridges, and Utahns Mignon Barker Richmond, Alberta Henry, Alice Kasai, Edith Melendez.

- Learn about additional Utah woman involved in the suffrage movement and in other advocacy work. Compare these women to Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, or Emmeline Wells. You might consider creating a dialogue or a sketch of a statue featuring these additional historical figures. What characteristics do these advocates all have in common?

- Consider a person alive today who is an “advocate for change.” How is the person similar and different to Anthony, Douglass, and Wells?

- Examine the arguments for abolition and for suffrage. How do these arguments compare? How do these arguments compare with arguments made in other social movements?

- Learn more about suffrage in Utah–how women in Utah were granted voting rights, had them taken away, and had to get them back. How does this story compare to the story of African-Americans gaining and losing rights in the United States? To Native Americans? Asian Americans? And to the national women’s suffrage narrative? Use the timeline on the home page for information and context. Or you may want to watch this short video (2:51) about the Utah women’s suffrage story.

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience

Statue of Anthony & Douglass

Statue of Anthony & Douglass