Additional Resources

George Sutherland,

U.S. Supreme Court Justice, U.S. Senator and Congressman, and Women’s Rights Advocate

1862-1942

“The right of women to vote is as obvious as my own.”

by Ann Engar

George Sutherland, the only Supreme Court Justice to come from Utah, supported women’s rights, particularly the right of women to vote and to engage as full members in American society. Sutherland was born in Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire, England, March 25, 1862, to Frances Slater and Alexander George Sutherland. The extended Sutherland family joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; and George and his parents traveled to Utah by ship, train, and wagon when he was only eighteen months old. Once in Utah, they settled in Springville, where George described his childhood as very simple and very hard. Because of his father’s problems with alcoholism, his parents left the church, and George was never baptized as a church member.

George quit school at age 12 and worked full-time to save money to attend Brigham Young Academy (BYA), a precursor to Brigham Young University. At age 16 he started at BYA, attended for two years, and then attended University of Michigan Law School for one year.

George Sutherland. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Returning to Utah, George married Rosamond Lee in 1883. They eventually became parents to three children. He practiced law with his father in Provo for three years, and then formed his own firm with Samuel Thurman in Salt Lake City. He entered politics, and in 1895 served on a commission drafting the Utah Constitution that provided for women’s suffrage, a cause which George would champion throughout his career.

In 1896, when Utah was admitted as a state to the Union, George, a Republican, was elected to the Senate in the first state legislature. In 1900, he was elected to Utah’s only U.S. Congressional seat, and in 1905, the Utah State Legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate, the method at the time for selecting U.S. senators.

Over the next decade, George became a leading figure in the national suffrage movement. Both he and his wife gave speeches and held meetings supporting the right to vote. The Sutherlands became friends with Alice Paul, the leader of the more radical Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, later the National Women’s Party, and helped her with events staged to garner support for the movement. In August 1915, women held a meeting in Salt Lake City to welcome Paul and her automobile train traveling from the Women’s Voter Convention in San Francisco to Washington, D.C. that gathered more than 500,00 signatures in support of a women’s suffrage amendment. At the meeting, Annie Wells Cannon, daughter of leading Utah suffragist Emmeline B. Wells, thanked George for his support, and he gave a few supporting remarks. When the train arrived in Washington, D.C. several months later, George and Wyoming Congressman Franklin Wheeler Mendell greeted it. On December 6, Representative Mendell introduced the Susan B. Anthony Amendment into the U.S. House, and the next day George introduced it into the U.S. Senate.

Senator George Sutherland, Winifred Mallon, Reverend Olympia Brown, Alva Belmont at the Utah State Capitol welcoming the suffrage envoys from the San Francisco Exposition that were carrying petitions to Washington D.C. in October 1915. Courtesy of the National Women’s Party.

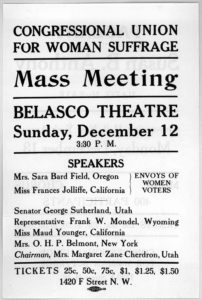

On December 13, Paul sponsored a mass meeting that took place at the Belasco Theatre in Washington D.C. with George as a main speaker. He based his arguments on the practical experience of the twelve states, including Utah, that had already granted the vote to women:

To my mind the right of women to vote is as obvious as my own right. . . When we have proven the case for universal manhood suffrage we have made clear the case for womanhood suffrage as well. Women on average are as intelligent as men, as patriotic as men, as anxious for good government as men, and to deprive them of the right to participate in the government is to make an arbitrary division . . . .

Flyer advertising Senator George Sutherland of Utah as a speaker for a mass meeting of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in Belasco, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

He closed by affirming that “women’s fundamental nature” would not change once they were given the right to vote; indeed, “it [voting] will deepen her sense of responsibility, give her a more intelligent appreciation of her country’s needs and broaden her opportunity to ‘do her bit’ for the common good.”

The amendment failed in 1916. George, too, suffered defeat after two terms in Congress, a defeat he felt came about because of his support for the amendment. He returned to legal practice and became President of the American Bar Association in 1918. He served as a campaign and later presidential advisor to Warren G. Harding. After the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, Alice Paul moved on to crafting the Equal Rights Amendment and consulted with George. Both agreed that the law should treat women and men equally no matter their alleged differences.

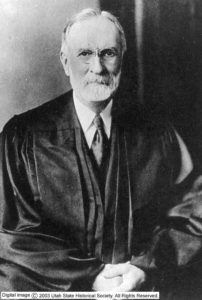

Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

President Harding appointed George an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1922, and he served until 1938. An opponent of Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, the conservative George became known as one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. His most important opinion was the majority opinion rendered in the case of Powell v Alabama, which helped lead to the constitutional right to counsel in all criminal cases and a recognition of the illegality of systematically excluding African Americans from juries.

George died July 18, 1942, while on vacation in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Ann Engar is a professor/lecturer in the Honors College and LEAP Program at the University of Utah, specializing in intellectual history, pedagogy, and law. She has authored numerous short biographies, including for the online NASW project, and serves on the Holladay Historical Commission.